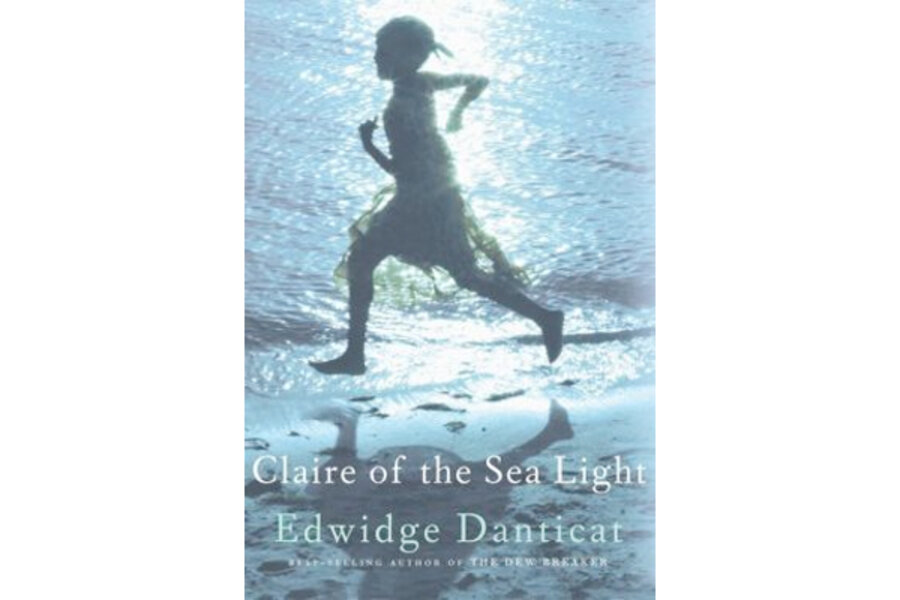

Claire of the Sea Light

Loading...

Claire Faustin has never had a happy birthday.

Her mother died the day she was born. Her father, Nozias, is an illiterate fisherman who lives in a shack on the beach in a seaside village in Haiti. Every year on her birthday, he tries to give the little girl to the fabric vendor, a wealthier woman who lost her own daughter, in hopes that Claire will have a better life.

“The good news, Claire thought, was that her father did not try to give her away every day. Most days he acted as though he would always keep her.”

On the day Claire turns seven, the fabric vendor says yes, and Claire disappears. Claire of the Sea Light, by Edwidge Danticat, traces Claire’s birthdays back in time in a series of interlocking stories about the residents of Ville Rose, a fictional town that Danticat first wrote about in 1995’s “Krik? Krak!”

“Ville Rose was home to about eleven thousand people, five percent of them wealthy or comfortable. The rest were poor, some dirt-poor.”

When one of the characters’ mothers is asked what she is doing, she tells them, “I am churning butter from water” – trying to make something from nothing.

The novel movingly traces the interconnected lives of Gaelle, the fabric vendor; Max Ardin, Sr., who runs the school where Claire attends on scholarship; his son, Max Ardin, Jr; their former maid, Flore Voltaire; Louise George, host of a call-in radio show; and Bernard Dorien, a would-be radio journalist and friend of Max Jr.

“Fok no voye je youn sou lot. We must all look after one another,” is a saying Claire’s mother was fond of. “Claire of the Sea Light” chronicles the ways in which the villagers look out for one another – and the ways in which they fail.

While Claire’s birthdays aren’t celebratory affairs – a visit to her mother’s grave, a trip to the fabric vendor to see if she’s being handed over – the girl herself is a source of joy. Her mother chose her name, Claire Limye Lanme, Claire of the Sea Light, and that luminousness fills the book.

Danticat, a 2009 MacArthur recipient and author of “The Dew Breaker” and “Brother, I’m Dying,” is, quite simply, one of the most beautiful writers working today. “Claire of the Sea Light” reads like a fable. The slender novel-in-stories is full of aphorisms and quiet wisdom.

In addition to the villagers, the sea, ever-present yet always changeable, also is a character in the book.

“People like to say of the sea that lanme pa kenbe kras, the sea does not hide dirt. It does not keep secrets,” Danticat writes.

As the book unfolds, some heartbreaking secrets come to light. Max Jr.’s mother, with whom he goes to live in Miami after perpetrating a crime, told him, “You are who you love... You try to mend what you’ve torn. But remember that love is like kerosene. The more you have, the more you burn.”

While in some of the villagers’ lives, that fire proves consuming, the book as a whole is lit by it.