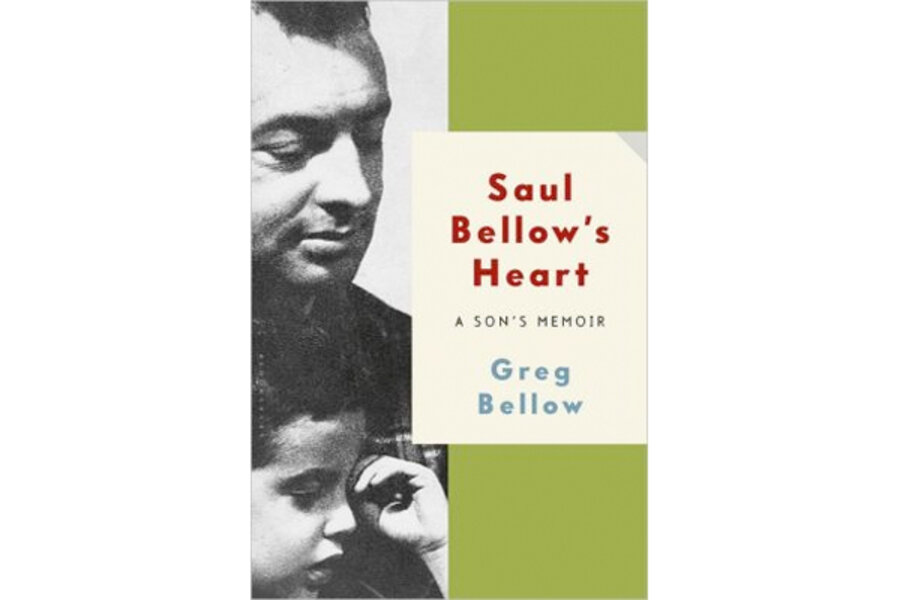

Saul Bellow's Heart

Loading...

Saul Bellow’s eldest son is a retired psychoanalyst, a profession that suited him because he was “able to relate to boys who suffered broken hearts,” Greg Bellow writes in Saul Bellow’s Heart: A Son’s Memoir.

The emotional anguish Greg suffered in childhood was the result of a father who pursued “a life where everything and everyone was subordinated to art,” who engaged in “epic philandering” that contributed to the dissolution of four marriages and drove a wedge between him and his firstborn child.

But Greg Bellow’s memoir is not a bitter screed about an absentee father who cared more about fictional creations than real people. It’s a balanced exposé of a Nobel Prize-winning author whose memorable, fallible narrators (including in “The Adventures of Augie March,” “Herzog,” and “Henderson the Rain King”) closely resemble Saul Bellow at various stages of his emotional and intellectual lives.

“My father’s novels are full of well-meaning friends, lawyers, schemers, and advisers brimming with helpful solutions for a series of narrators. Like Saul, his narrators usually ignore the advice and follow their own misguided efforts, which draw them into a destructive vortex.”

Bellow’s oeuvre has been examined many times by literary critics and biographers, but his son has unique insights into the author’s heart, born of long conversations over many years about topics that a less liberal parent would have avoided.

“Beginning in my adolescence, when the two of us were alone, my father would inquire after what he termed my inner life. Initially I was a bit confused, but soon realized he was asking me to consider whether or not I was content with myself. This began a regular dialogue we came to call ‘real conversations.’… they became a regular feature of our time together.”

The relationship between Greg and Saul is informed by Saul’s difficult relationship with his own father, Abraham, whose “failure to earn an adequate income aggravated his already volatile temper. He often blamed parenthood for his impoverishment and gave each of his boys a whack to cover their presumed sins when he got home from a day of hard work.”

Abraham thought Saul was emotionally soft, and he pressured his youngest son to enter the family’s coal business.

“When Saul resisted, Abraham derided him and his bookish friends with a vacuous tongue.”

Saul can be equally biting in his criticism, Greg writes, but he was not physically abusive.

“In conscious contrast to his father, Saul took pride in not hitting me and made a point of telling me so.”

And yet Saul’s abuse could be emotional and intellectual, as he took little interest in Greg’s career and acted recalcitrant towards other family members and longtime friends.

“[H]is self-justification: that his career as an artist entitled him to let people down with impunity.”

Which isn’t to say that Saul wasn’t betrayed by those closest to him, too. His second wife had a longtime affair with his best friend, and his son even now struggles to understand how his father could have been so deceived.

“The answers lie in his facility with logic, his inclination to trust, and his inability to see guile in others that his hardheaded older brothers would never have missed.”

Understanding Saul’s difficult relationships with women is central to understanding the man and his fiction, his son writes. Like Augie March, Saul was “adoptable,” and his demeanor “communicated a hint of softness and pliability that drew out protective feelings in women along with the illusion that they could shape Saul into what they wanted him to be.”

The illusion never lasted. And the young, dashing Saul, who was rebellious and humanistic, became more conservative and paternalistic with age, much to his son’s chagrin.

Changes also took place in how Saul was seen by others, particularly younger writers like Martin Amis and Jeffrey Eugenides, who knew Saul mostly through his writing. When Saul died in 2005, Greg felt shoved aside by these literary sons of Saul Bellow.

“As Saul’s firstborn, I believed our relationship to be sacrosanct until his funeral, an event filled with tributes to his literary accomplishments and anecdotes about his personal influence on those in attendance that set in motion my reconsideration of that long-held but unexamined belief.”

Ironically, he decides that the best way to examine his relationship with his father is by reading his father’s books. In the end, he knows that’s where Saul Bellow’s heart can be found.

Cameron Martin is a Monitor contributor.