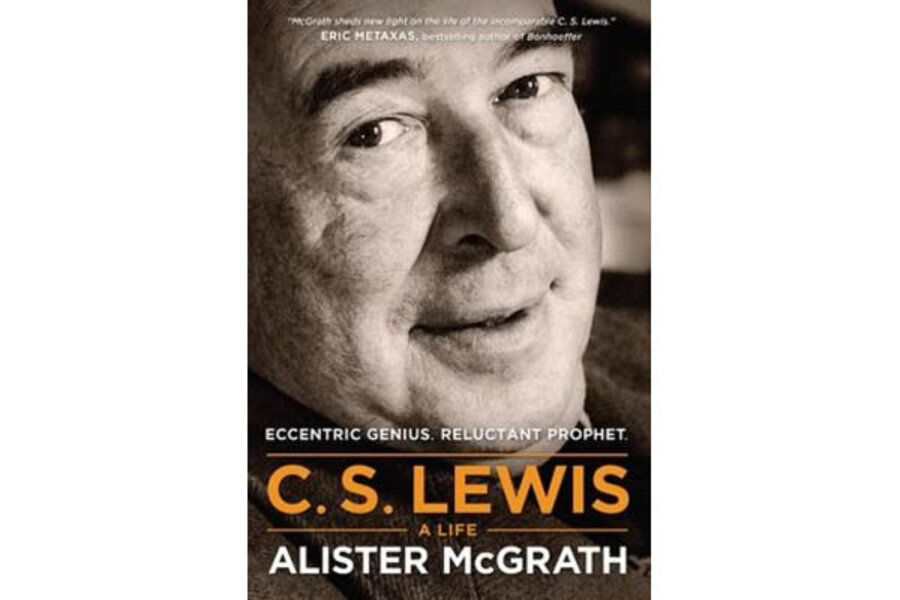

C.S. Lewis: A Life

Loading...

When C.S. Lewis died in England on Nov. 22, 1963, the world took little notice. President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated on the same day, and most people focused on the slain American leader instead. Also diminishing attention on Lewis’ death was the decline of his literary reputation at the time. Amid the rapid cultural changes of the 1960s, Lewis seemed to many a man of yesterday.

What a difference five decades make. Today, Lewis appeals to thousands of readers around the world for his philosophical books about Christian faith, his science fiction tales, and highly allegorical children’s stories such his Narnia chronicle, beginning with the iconic fantasy, “The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe.”

This year’s 50th anniversary of Lewis’ death promises to raise even more awareness of a popular apologist for Christian doctrine. In conjunction with the anniversary, author Alister McGrath has released a new C.S. Lewis biography, with a companion volume on Lewis’ thought due out later this year.

C.S. Lewis: A Life follows in the footsteps of several other Lewis biographies, some of them penned by friends and acquaintances of the famous writer. “Unlike his earlier biographers ... I never knew Lewis personally,” McGrath tells readers. “I have no illuminating memories, no privileged disclosures, and no private documents on which to draw.... This is a book written by someone who discovered Lewis through his writings, for others who have come to know Lewis in the same way.”

Making a virtue of necessity, McGrath attempts to offer a critical perspective on Lewis in lieu of firsthand testimony, a strategy that emphasizes scholarship rather than chatty anecdote. McGrath proves copious in his research, although his narrative method tends to keep Lewis at arm’s length.

McGrath is fond of using the editorial “we” in his sentences, as if he’s implicating the reader in an extended classroom lecture. It’s a way of writing that routinely points to McGrath as the narrator of the story, rather than to Lewis, the man ostensibly at the center of the book. What one misses in “C.S Lewis: A Life” is the cunning illusion promised by the best biographies – the feeling that one is immersed within a life as it’s being lived.

But McGrath is nothing if not thorough, taking full advantage of some recent resources not available to earlier biographers. Most notable is the extensive collection of Lewis correspondence published between 2000 to 2006. “These letters, essential to Lewis scholarship, form the narrative backbone of this biography,” McGrath writes.

Most of the story in McGrath’s book will be familiar to readers of earlier Lewis biographies. Born in Belfast in 1898 to an upper middle-class family, Lewis spent his childhood in a rambling house that had more than a passing resemblance to the setting of “The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe.” The tranquility of Lewis’s early youth gave way to turmoil when his mother died, prompting his father to place him in a series of oppressive boarding schools. Isolated, Lewis took solace in books, giving himself the first lessons he’d use in a career in letters. Eventually, Lewis found a mentor in William Thompson Kirkpatrick, a former school master whose cultivated skepticism fueled Lewis’ growing doubts about orthodox religion. Lewis became an atheist, a position he retained into his early academic career as a scholar of English literature at Oxford.

McGrath, who admits to following a similar path from skepticism to religious faith, seems most engaged at the midpoint of “C.S. Lewis: A Life,” when he carefully charts Lewis’s evolution from nonbeliever to fervent Christian thinker in the years between 1930-1932. McGrath points out that Lewis’ conversion was part of a larger wave nudging fellow intellectuals such as T.S. Eliot and Evelyn Waugh into the church. Lewis, says McGrath, “fits into a broader pattern at this time – the conversion of literary scholars and writers through and because of their literary interests. Lewis’s love of literature is not a backdrop to his conversion; it is integral to his discovery of the rationale and imaginative appeal of Christianity.”

McGrath’s observation is central to his biography, which suggests that the best way to understand Lewis is to know what he read and wrote. The most abiding gift of “C.S. Lewis: Life” is its fierce curiosity about the novels, letters, and books of popular philosophy that are Lewis’ most substantial legacy. McGrath’s biography promises to introduce new readers to those works – and inspire veteran C.S. Lewis fans to visit them again.

Danny Heitman, an author and columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate, is an adjunct professor at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication.