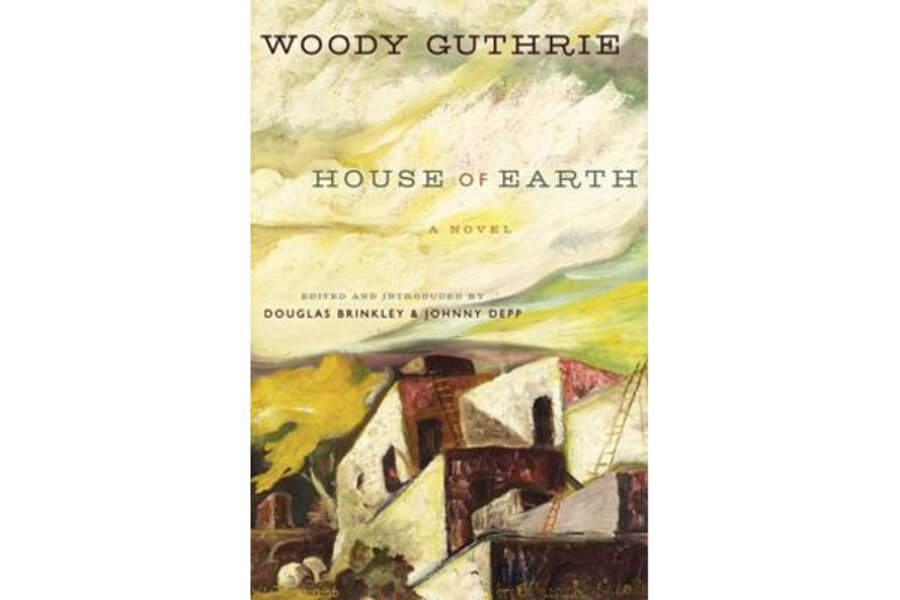

House of Earth

Loading...

Though John Steinbeck might be considered the unofficial chronicler of Dust Bowl-era America, folk singer Woody Guthrie certainly occupies a firm place in the pantheon of artists with something to say about that world. While Guthrie has thus far been renowned as the writer of thousands of songs and as a champion of the proletariat, he’s belatedly getting another accomplishment added to his bio: published novelist.

Guthrie published a memoir and a fictionalized autobiography in his lifetime, but never sought to publish his only novel, House of Earth. But now history professor Douglas Brinkley and actor Johnny Depp have worked together to bring the story to publication. They say they’ve made only cosmetic changes and restructured two paragraphs from the recently rediscovered manuscript.

The novel follows Tike and Ella May Hamlin, two dust bowl farmers in the Texas panhandle striving to survive in a ramshackle wooden house on land they don’t own in an unforgiving climate. One day, Tike comes home with a book from the government about how to construct an adobe house, the titular house of earth. Their one-room, run-down house doesn’t keep hot or cold out, but the new adobe house would be cheap and easy to build, and promises a new beginning for them.

Then there’s a lengthy, graphic sex scene. The delay in publishing the novel, completed in 1947, becomes more understandable.

“House of Earth” is a trifle short on plot. When a third character appears (Blanche, a nurse, there to help Ella May with a pregnancy), she is the final character.

Tike doesn’t necessarily have any revolutionary ideas to improve the family’s economic status. His plans are essentially adobe house, then happiness. Ella May, by turns charmed and exasperated by his single-mindedness, hates their dilapidated house, and can barely be convinced to give birth in it, rather than outside during a blizzard. The ending does not offer up any promises that life is necessarily going to improve for their little family, though the two of them are determined to make that happen.

Guthrie himself was reportedly equally enamored of the adobe house idea, going so far as to say that man himself was an adobe house, “some sort of a streamlined old temple.” The book’s foreword, written by Brinkley and Depp, explores in detail his fascination with the concept, inspired by an actual US Department of Agriculture booklet.

The book swings back and forth between an earthy, lived-in tone, full of good-natured teasing and the slang and rhythms of Guthrie’s home, and a more pedantic nature, with the two main characters sounding like mouthpieces for Guthrie’s beliefs about capitalism and farming. The two joke and tease much like a real-life couple, but they also talk about the meaning of land ownership immediately after the birth of their child.

Guthrie demonstrates an easy facility with language and the words of the people of the Great Plains. The opening lines strike a note of simple poetry that promises more, perhaps, than Guthrie is able to offer in total: “The wind of the upper flat plains sung a high lonesome song down across the blades of the dry iron grass. Loose things moved in the wind but the dust lay close to the ground.”

Images like these speak to Guthrie’s ability to recreate the dust storm-plagued days of his youth in the Texas panhandle, and in those early moments, the book shows a great deal of promise. It's intriguing to wonder what the book might have become had its author had a firm-handed editor to help him complete it.

As it is, the book remains readable, and full of glimpses into the Woody that inspired so many leftists over the years. Tike, a bit of a goofball, rags on Blanche, the nurse, for having gone to college, but then acknowledges to himself that women should be going to college and getting degrees. Was this a popular opinion among men in the 1940s?

If Steinbeck was the chronicler of people who fled west for better opportunities, Guthrie wishes to speak up for all the people who chose to stay behind in the ravaged lands of the Great Plains. It was the land of their parents and grandparents, and owning a piece of it seems like the greatest, but most unreachable, goal they can imagine.

"House of Earth" will certainly be essential reading for Woody Guthrie fans. The likelihood of its becoming a classic of American literature is less than one might have hoped. But the novel does serve as a rare glimpse into lives lived on the narrow edge of poverty during a dark time for the country.

Lisa Weidenfeld is a Monitor contributor.