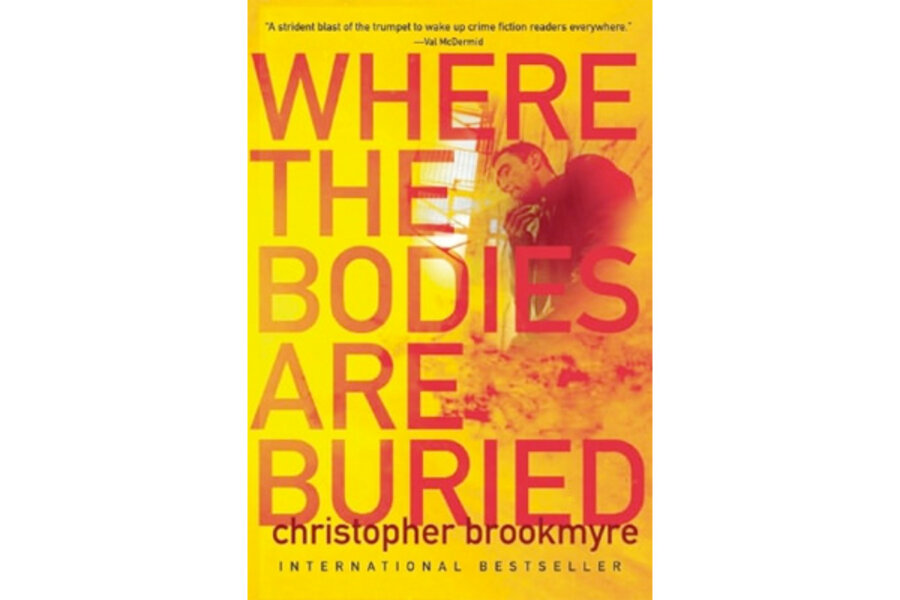

Where the Bodies Are Buried

Loading...

The title of a Christopher Brookmyre novel often tells you a lot. "All Fun and Games Until Somebody Loses an Eye," for example, or "A Big Boy Did It and Ran Away" seem to promise anarchic violence, quirky characters, and ironic humor. Tough Scottish humor, as it happens, leavened with Elmore Leonard-like flourishes. Brookmyre's latest novel, Where the Bodies Are Buried, sounds straightforward by comparison, and thankfully it is. Brookmyre is at his best when he writes plainly instead of straining for noir effect.

Here he first describes his city, in summer. "It didn't seem like Glasgow," he writes, "...the clouds had rolled in on top of a sunny day like a lid on a pan, holding in the warmth, keeping hot blood on a simmer." He then introduces the city's leading gangsters as they stand around a beaten drug dealer who is about to be shot in the head. There is Big Fall, Wee Sacks, and the Gallowhaugh Godfather, who looks "older even than his scarred and lived-in face would indicate; a face you would never get sick of kicking."

Gangland politics may have prompted this killing, while police politics are a separate matter – or are they? When Detective Superintendent Catherine McLeod begins to investigate the squalid assassination, her search soon leads into the shadows where filthy deals are made between cops and villains. This is a shock, but not a revelation, to a woman who has seen it all. Observing a new colleague as they drive to the murder scene, McLeod notes, "The girl was keen, give her that, but the guy would still be dead when they got there." Brookmyre's laconic humor freshens a potentially stale character – the female police officer who is also a wounded child, an exhausted mother, and an insecure lover – and also jolts the narrative out of its predictable ruts. When McLeod is called to a fire-gutted building owned by a crime boss, for example, she muses that "Frankie wouldn't be losing any sleep over it. What with being dead and all."

The intrigue has, by this stage, thickened nicely as Brookmyre skillfully develops two parallel plots that must eventually overlap, although we cannot see how. While McLeod wades deeper into gangster and police skullduggery, a neophyte private investigator tries to find out why her boss has suddenly disappeared. Young Jasmine Sharp is an aspiring actress and an innocent, bereft without her recently dead mother and now adrift without her employer (who is also her uncle Jim). "She didn't have a life yet," she realizes. "There was no saddle for her to get back into."

All Jasmine can do is follow the leads that Jim was following. One reaches back twenty-seven years to the unexplained disappearance of a young couple and their baby. Another, more chillingly, brings Jasmine into the life – and under the protection – of Tron Ingrams, a soulful man with a bloody past. "I need to put a name to my sins," he tells Jasmine, "and I need to wear that name." Which is a portentous way of saying that he is not Tron Ingrams. His true identity cinches together strands from the past and present, some of which should have been left dangling. A tidy outcome is an unconvincing conclusion to the finely controlled yet exuberant mayhem that Brookmyre has kicked up.

Anna Mundow, a longtime contributor to The Irish Times and The Boston Globe, has written for The Guardian, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, among other publications.