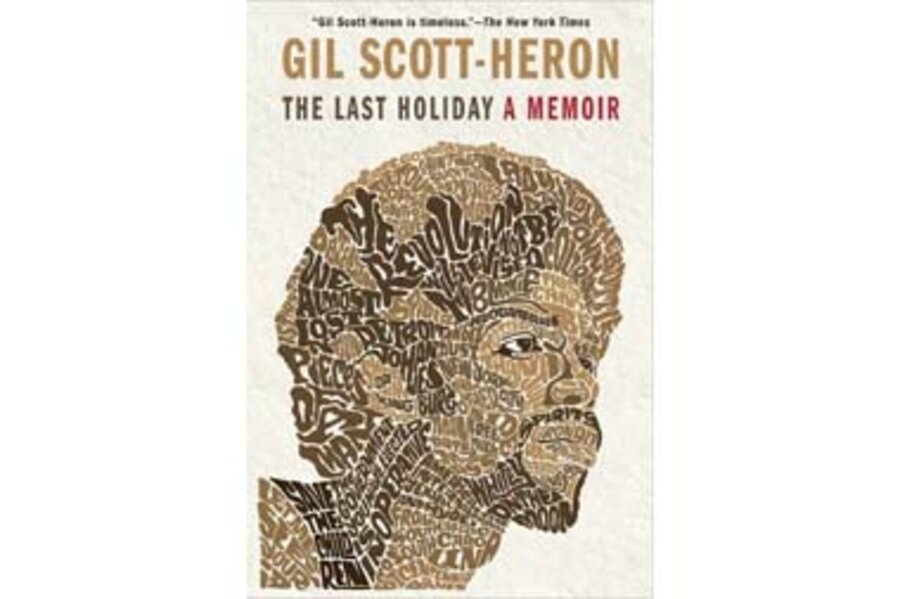

The Last Holiday: A Memoir

Loading...

Gil Scott-Heron was not the Godfather of Rap. But when he passed away last year at the age of 62, nearly every obituary honored him as such. His posthumously published memoir, The Last Holiday, unsurprisingly touts Scott-Heron's hip-hop connections as well, with back cover blurbs from Chuck D, Common, Eminem, and others. But never in the book's 321 pages does Scott-Heron mention the words rap or hip-hop.

To term Scott-Heron's music as proto-rap is to misapprehend the nature of his broad influence upon the freewheeling space of American culture and the particularly liberated zone of African-American music. Scott-Heron was just as much an aggregator of influence as he was a purveyor of it. Seeing him in concert, one might hear the preacherly inflections of the Baptist pulpit, the stand-up insouciance of a young Bill Cosby, and the smoothed-out patter of a late-night radio DJ, all woven together.

Rap carries on only a part of Scott-Heron's legacy. "I've always looked at myself as a piano player from Tennessee; I play some piano and write some songs," Scott-Heron writes with characteristic humility and directness. Scott-Heron was a musical surrogate father of sorts: to hip-hop as well as to the spoken-word movement; to black rock, funk, and folk; and to a host of politically minded and soulful artists who, like the man himself, defy the tidy characterizations of genre.

On every page, "The Last Holiday" proves that to understand Gil Scott-Heron's life, you must embrace his music. His sound is polygeneric, mixing soul, blues, jazz, funk, folk, rock, and even a little reggae. "We are miscellaneous," Scott-Heron was fond of saying. On songs like "Is That Jazz?", he lampoons those frustrated by their inability to pigeonhole him. Though unclassifiable, his style was equally unmistakable: "a voice," Scott-Heron writes, "with a low end that rumbles along like a subway car with a flat wheel." What defined his aesthetic above all else was his refusal to admit barriers. A writer, a poet, a spoken-word performer, a lyricist, a musician, a singer – Gil Scott-Heron demands to be seen as nothing less capacious than an artist.

For all of this, his body of work is often reduced to a single stance of protest and even a single song, the iconic "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised", which he first recorded at age 19. Even a cursory glance through his catalog, however, reveals that he and his composing partner, Brian Jackson, wrote songs about so much more than politics – partying, loving, mourning, remembering. "I felt people who wrote about me and Brian should have looked at all that we did," Scott-Heron asserts. "It was pretty obvious that there was an entire Black experience and that it didn't relate only to protest. We dealt with all the streets that went through the Black community and not all of those streets were protesting."

Though Gil Scott-Heron lived – and even toured – until the spring of 2011, he chooses to frame his memoir around events that occurred in 1981. That year Scott-Heron stepped in as the opening act for an ailing Bob Marley, on Stevie Wonder's Hotter than July tour. Far more than music was at stake. The tour also served as a nationwide barnstorming campaign in support of a Martin Luther King, Jr. observance – something Wonder passionately advocated in his song "Happy Birthday".

The "last holiday" of the book's title refers to the adoption, just two years after Wonder, Scott-Heron, and others made their case, of Martin Luther King Day as a federal holiday. But one can't help also reading the title with other lasts in mind: word, hurrah, will and testament.

Closing his book at this transitional moment – the dawn of a decade, the beginning of a new presidential administration, the end of a musical era – makes perfect sense on an organizational level. It also allows Scott-Heron to evade the messiness of the three decades that followed, which would see him struggle with addiction and depression.

One can easily imagine quite a different book emerging from the material Scott-Heron's life provided him. It might have read something like a first-person rendition of the New Yorker profile from August 9, 2010, which focused on his struggles with crack addiction. This could have been the memoir of a bitter man, turned against himself and the world around him. Indeed, from the outside looking in, the arc of his life seems bent toward tragedy.

The Last Holiday centers instead on celebration. Even the darkest chapters of his past – his absentee father, his childhood estrangement from his mother, his setbacks on his road to success – are rendered without self-pity. On the page, Scott-Heron's voice is by turns witty and insouciant, wise and humble. The book achieves what the best memoirs always do: It reveals the author as a familiar; it fosters empathy across distance.

But like Scott-Heron himself, his memoir is at times prone to excess. He has a taste for extravagant similes, some of which come across as contrived. A pause in conversation, for instance, "hung in the air between us like a condor" and a New York City winter is "as cold as a whore's heart." More often, though, his writing remains in key. He displays a remarkable ability to sketch a character in a single line, as he does when he describes his Uncle Buddy as "a sober elder statesman who never said four words when three would get it said."

"The Last Holiday" is a feel-good story written by a man who knew what it was to feel bad. Read it with Scott-Heron's music in your ears (try 1974's Winter in America to start). Read it with an open mind. If he can produce such light amid the darkness that surrounded him, then the least we can do is let that light shine in.

Adam Bradley is the author of "Ralph Ellison in Progress" and the co-editor of "Three Days Before the Shooting...," the posthumous edition of Ellison's unfinished second novel.