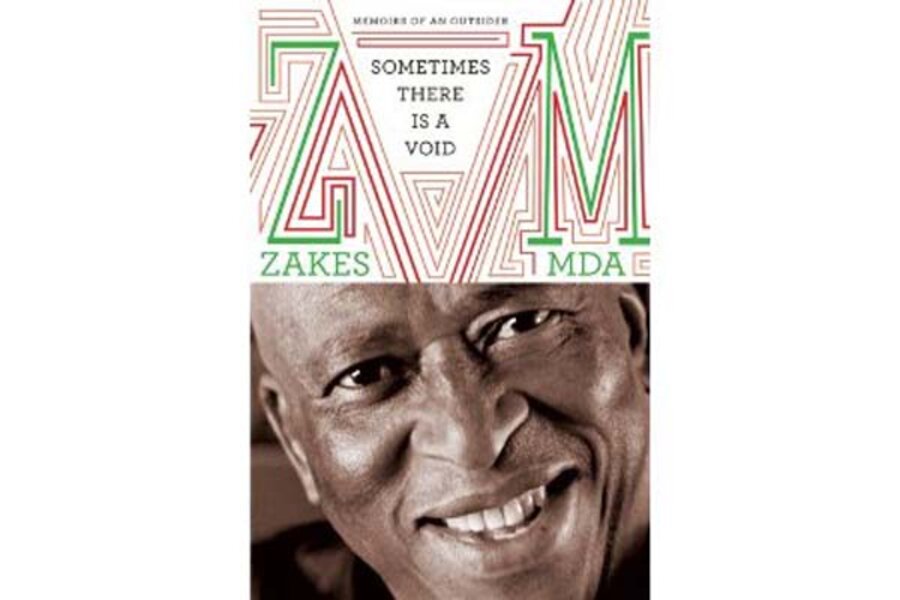

Sometimes There Is a Void

Loading...

Zakes Mda’s life story, Sometimes There is a Void, is a fascinating shambles.

Mda is born the awkward son of a political activist who walked with revolutionary giants. He grows up too fast in political exile in Lesotho, straying for a time as a drunken wastrel. He eventually finds his place in the world as a talented young novelist and playwright who realizes the best way he can serve his people is to give them a voice. In a racist world that viewed black South Africans as ill-educated brutes, Mda helped to change the narrative, creating complex characters who forced outsiders to rethink their misinformed prejudices.

During my five-year stint as Africa bureau chief for The Christian Science Monitor, I struggled in vain to find a memoir like this one. Bookstores in Johannesburg and Cape Town were full of memoirs, to be sure, from Nelson Mandela’s “Long Walk to Freedom” and Ahmed Kathrada’s “Memoirs,” to Rian Malan’s poignant “My Traitor’s Heart” and Antjie Krog’s “Country of My Skull.”

But while the vast majority of South Africa’s citizens are black, the vast majority of South Africa’s authors tend to be white. Liberal as those white writers may be – and authors such as Alan Paton, Doris Lessing, Andre Brink, and Nadine Gordimer do an excellent job of portraying well-rounded, compelling black characters – there is nothing that can replace a black person telling his or her own story, the pain of living under apartheid, and the joys, hopes, and disappointments of living in a post-apartheid majority-led South Africa.

A well-told biography is more powerful than a nuclear weapon. It can level the mental playing field, show the human commonalities that all communities and ethnicities share. It can melt hearts, create empathy, and show racism to be as stupid as it clearly is.

Friends of mine who had served in the African National Congress’s military wing, Umkonto we Sizwe, told me they studied the 1929 journal of Deneys Reitz, “Commando,” while they themselves trained as soldiers in exile in Tanzania, Zambia, and Libya. While they were preparing for battle against an Afrikaner-led apartheid government, they sympathized with the young Afrikaner militant’s struggle for self-rule in a British-dominated South Africa during the Boer War; they also appreciated Reitz’s handy descriptions of guerrilla warfare tactics against the British, which the ANC in turn used against the apartheid government.

Zakes Mda – who now teaches at Ohio University – is known for writing tightly crafted novels. “Sometimes There is a Void” is not his best effort. The stories he tells are funny, and sometimes horrifying. There are uncomfortable bits – from Mda’s experience of being sexually abused by his nanny at an early age to his bouts of alcoholism – that are not easy reading. I personally squirmed as Mda described his relationship with his father, the attorney Ashby Peter Mda, who served with Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu in the African National Congress, but later broke away to join the more radical Pan Africanist Congress. Tata Mda was a tough customer who tended to lecture his family at the dinner table, charged so little for his services that his family constantly had money problems, and never gave his children the warmth they craved. But reading about him, I heard echoes of other revolutionaries – such as Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi – who also sacrificed their family duties for a national cause.

Mda deserves praise for telling his story in full, without editing out the ugliness. But Mda’s story feels like a first draft. By taking out the red pencil and cutting an anecdote here, a decade there, he would have focused more attention on the three or four take-home messages he most wanted to leave behind. Some readers will have enough patience to read this book all the way through. They’ll have much to laugh and cry about.

But Mda would have won a much larger audience with a much smaller book.

Scott Baldauf, a Monitor staff editor, was the Monitor's Africa bureau chief for five years.