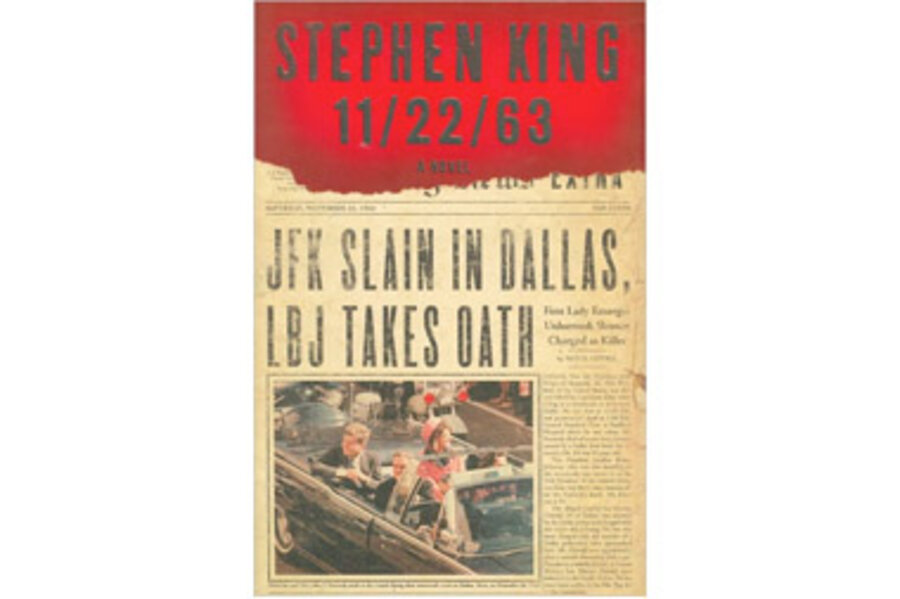

11/22/63

Loading...

Leave it to Stephen King to take one of the greatest horrors of the 20th century – JFK’s assassination – and make it even worse by undoing the entire episode.

Spare Kennedy from Lee Harvey Oswald’s bullet at Dealey Plaza in Dallas and prepare for former Alabama Governor George Wallace to become the 37th president.

His election follows an era devoid of Civil Rights triumphs. In King’s alternate take, LBJ’s mastery of legislative power remains untapped in the office of the vice president.

“The Republicans and Dixiecrats filibustered for a hundred and ten days; one actually died on the floor and became a right-wing hero,” he writes. “When Kennedy finally gave up, he made an off-the-cuff remark that would haunt him until he died in 1983: ‘White America has filled its house with kindling; now it will burn.’ ”

Such stomach-churning fun-house mirror episodes loom among many unintended consequences in 11/22/63, a piece of time-traveling historical fiction that makes the what-if game intensely personal and terrifyingly broad all at once.

It begins with the owner of a small-town diner in Maine named Al Templeton, who is dying of cancer. Locals have long wondered about Al’s Diner because of its Fatburgers, priced to move at $1.19.

Unknown to all but Al, the pantry of the diner just happens to be a portal into the past. 1958, to be specific. Rather than serving catburgers, as many in town have conjectured, the proprietor has been stepping into the past and buying ground beef for 54 cents a pound in the sock-hop era and bringing it back into 2011 for a healthy profit margin.

Cheap burgers are well and good, but the rabbit-hole inspires more than just business schemes. Each time Al Templeton returns to 1958, no matter how long he stays, just two minutes have elapsed in the 21st century when he returns. All of which can get a man’s mind to thinking.

The thinking Al does turns to history. Rewriting one of the saddest episodes in American history becomes an obsession for Al as he ponders what it would take to kill Oswald before Oswald can kill President Kennedy.

Near death, Al enlists Jake Epping, a 35-year-old high-school English teacher with a penchant for burgers, by initiating him into the otherworldly pantry and the plot to change American history.

This, of course, provides the foundation for the classic King tale: an ordinary man engulfed in the most extraordinary of circumstances.

King, a 64-year-old Baby Boomer, has a Mad Men-style ball satirizing the past as he sends a thoughtful but average man hurtling 53 years into the past. Before the harsh retaliation of mucking with the universe hits with full force, Jake Epping emerges enthralled and appalled during his initial sojourns into the Eisenhower era.

A trip down the pantry steps takes Jake from 2011 Lisbon Falls, Maine into Lisbon Falls on Sept. 9, 1958. Armed with $9,000 in period-vintage bills provided by Al, Jake discovers a country befogged by cigarette smoke, from restaurants to buses to the Steve McQueen TV ads for Viceroy. Homophobia, sexism, and anti-Semitism, not to mention blatant racism, run rampant.

Gas costs 20 cents per gallon. Hawaii has yet to become a state. At the drive-in, the double feature is tough to beat: Paul Newman in "The Long, Hot Summer" and Alfred Hitchcock’s "Vertigo" with Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak.

Food tastes better because it’s not processed to death. (Then again, there are downsides in the diet department, as Jake notes: “Probably a billion grams of cholesterol in every bite, but in 1958, nobody worries about that, which is restful.”) For $315 and a little haggling, Jake snaps up a 1954 Ford ragtop.

King enjoys the pop-culture ride, with nods to the Everly Brothers and the McGuire Sisters, among many others. For aficionados, the author slips in a delightful aside with a nifty cameo of characters and incidents from his 1986 novel “It” as Jake wanders through small-town Maine in the '50s.

In a world without cell phones and the Internet, Jakes faces constant fears of anachronism living in the past.

Just ordering a beer can be tricky. When Jake asks for a Miller Lite, the bartender replies, “Never heard of that one, but I’ve got High Life.”

Later, after migrating to Texas, Jake absent mindedly sings the Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women” in front of his girlfriend. When she asks where he heard such filth, Jake says the radio, an answer she can’t fathom in the still-staid early 1960s. It is still a time when Americans have no idea who Mick Jagger and Keith Richards are and, even if they did, they wouldn’t dare to hum along to lyrics about a “gin-soaked barroom queen.” At this point, the Beatles are still a few years away from arriving on Ed Sullivan’s stage.

Jake, of course, has advantages of his own, such as knowing the outcome to Kentucky Derbys, World Series (the Pirates’ 1960 stunner over the Yankees comes in handy), and other sporting events of his newfound present-day.

Al spent several years in pursuit of Oswald, traveling to Texas, taking notes on what he found. Ravaged by cancer, Al kills himself, leaving the fate of JFK and Oswald in Jake’s shaky hands.

With that, King ratchets up the consequences of changing the past. Jake ponders the butterfly effect and wonders constantly whether the small changes wrought by his presence are altering future events in unexpected and harmful ways.

He finds the past stubbornly resistant to going off-course, though the lax world of a half-century ago lends itself to creating false identities with minimal inconvenience. Driver’s licenses, for example, don’t include photos. Travelers can walk into an airport and hop on a plane, no questions asked. And, as Jake demonstrates, a gun can be legally and legitimately bought for $9.99 with no waiting period required.

Jake’s mission to save JFK depends on him answering a question that has vexed Oliver Stone and Kevin Costner, among many others. That is, did Oswald act alone or was it a conspiracy involving the Mob, the government, or others? Jake heads South from Maine, witnessing Jim Crow on his way to Florida before migrating west to New Orleans and then into the hostility of Dallas in the early 1960s.

King inserts plenty of verisimilitude into his tale, the result, no doubt, of many virtual and actual trips to Dallas and the Sixth Floor Museum. Most important, the Oswalds and Kennedys are living, breathing people rather than historical artifacts. For a time, Jake lives below the Oswalds in an apartment on West Neely Street (where Lee and Marina Oswald lived with their baby daughter) and tries to determine whether Oswald is the lone conspirator.

When he’s not chasing Oswald, Jake retreats to a small town outside Dallas and stumbles into what would be an idyllic job and romance sullied by just one unavoidable exception: He’s a time traveler from the 21st century trying to save the president’s life. Even if he wanted to enlist help, no one would believe the outrageous scenario of what history will record on Dallas’ day of infamy.

Somehow, the absurdity of the situation – and Jake’s self-awareness – makes the love story all the more heartbreaking. These threads eventually come together (King has never been a man to be hurried through a tale and that holds true here) in a breathless chase to reach the Texas School Book Depository on a November afternoon when JFK and Jackie are basking in the sun in an open-air car.

“The noise of the crowd rushed in again, thousands of people applauding and cheering and yelling their brains out,” Jake recalls. “I heard them and Lee did, too. He knew what it meant: now or never. He whirled back to the window and socked the rifle’s butt-plate against his shoulder.”

And with that, King’s muse dances through several twists in a finale that makes 11/22/63 a date well worth keeping.

Erik Spanberg regularly reviews books for the Monitor.