The Promise: Year One of the Obama Presidency

Loading...

As someone who admires Barack Obama and worked for a year on his presidential campaign, I find it hard to understand the depth of the anger he has inspired on the political right. His policies are left of center but hardly extreme, and by themselves don’t explain why a small but significant portion of the country sees in his ascent to power the end of life as we know it in America.

Given this puzzle, other explanations for the vitriol have been proposed: that his skin color, middle name, or elite bearing incite a visceral response in people who consider him to be different from themselves. These strike me as relevant considerations, but I think they stop short of fully explaining phenomena like the “tea party.”

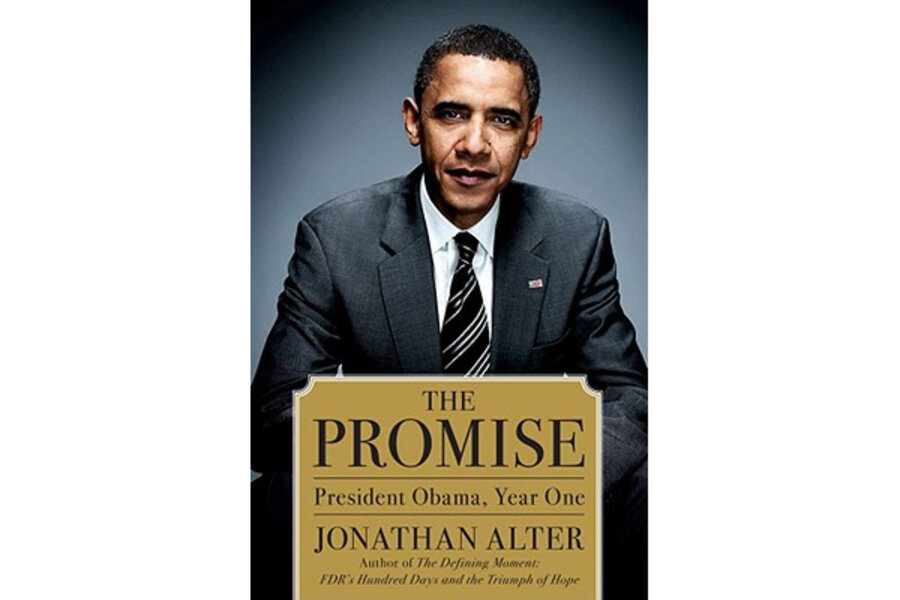

The gap between the apoplectic rhetoric and the reality of the Obama administration seems even more pronounced after reading Newsweek columnist Jonathan Alter’s new book The Promise, which depicts Obama’s first year in office as a clinic in sound decisionmaking. Obama is seen shuttling between policy meetings that he concludes by enumerating “take home” messages, and his study where he reads briefing binders late into the night. While George W. Bush may have been our first president with an MBA, it is Obama who seems to have absorbed the management practices taught in business schools. The result is a White House that feels wonky, competent, slightly claustrophobic, and even a little boring, but never revolutionary.

Yet there is clearly something else going on. In an interview with Alter, Obama describes his approach to policymaking as a search for the correct answer to a problem. In this view, if you ask analytic questions, collect good information, and strip away ideological predilections, the right policy choices for America should become self-evident.

But Alter is correct to ask, “a right answer for whom?” As the health-care debate demonstrated, it’s possible for both parties to take a clear look at the facts and come to different conclusions about what’s best for the country. Though there was plenty of political hoopla around the issue, it was also true that Democrats and Republicans assigned unequal values to the goal of achieving universal coverage; the question ultimately turned on core values, and no briefing book was going to be able to say which approach was the wiser.

During the 2008 campaign, Obama was covered from more angles than any presidential candidate has been before. Despite that, I never managed to understand where his ambition comes from. With George W. Bush and Bill Clinton, I got it – their runs for office made sense to me in a certain intuitive way – but with Obama, I could not figure out what drove him, such that he was willing to upend his life and spend so many days away from his kids. I’ve never been able to reconcile his self-possession with his pursuit of an office that I think of as the provenance of more obviously grasping men.

The answer is not forthcoming in “The Promise,” either. The book takes a necessarily nearsighted perspective on events that only recently happened, like Obama’s decision to escalate in Afghanistan and to pursue health- care reform over the objections of his senior advisers. There are moments of synthesis – Alter concludes that, contrary to the campaign critique of Obama as all style and no substance, he has turned out to be an even better executive than he was a candidate – but on the whole the narrative sticks to facts and anecdotes, many of which will be familiar to anyone with an RSS feed stuffed full of political news.

One story from “The Promise” that was news to me involved the dig Obama delivered during his nomination battle with Hillary Rodham Clinton, when he said that Ronald Reagan had been a transformational president, but Bill Clinton had not. The remark received a lot of attention at the time and I had assumed it was an example of Obama the intellectual ruminating too freely. But Alter reveals that in fact it was a well-conceived gambit designed to provoke a response from the proud Clintons. (And it worked – over the next weeks an unhinged Bill Clinton effectively tanked his wife’s campaign.)

This episode illustrates two things about Obama that I think keep the tea partyers up at night. The first is that he’s very good at politics. The second is that by parsing the difference between Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, Obama made it clear that he, too, aims to have a transformational effect on America. But transformational in what direction? The postpartisan mirage – if Obama ever really believed that would be his legacy – has been exposed as such. Obama is content for now to present himself as a technocrat solving problems, but one suspects that he has a grander design in mind. For those who have faith in him, this is the promise of his presidency. But for those who don’t, this is the real threat, that the best player at the table has not yet shown all his cards.

Kevin Hartnett is a freelance writer in Philadelphia.