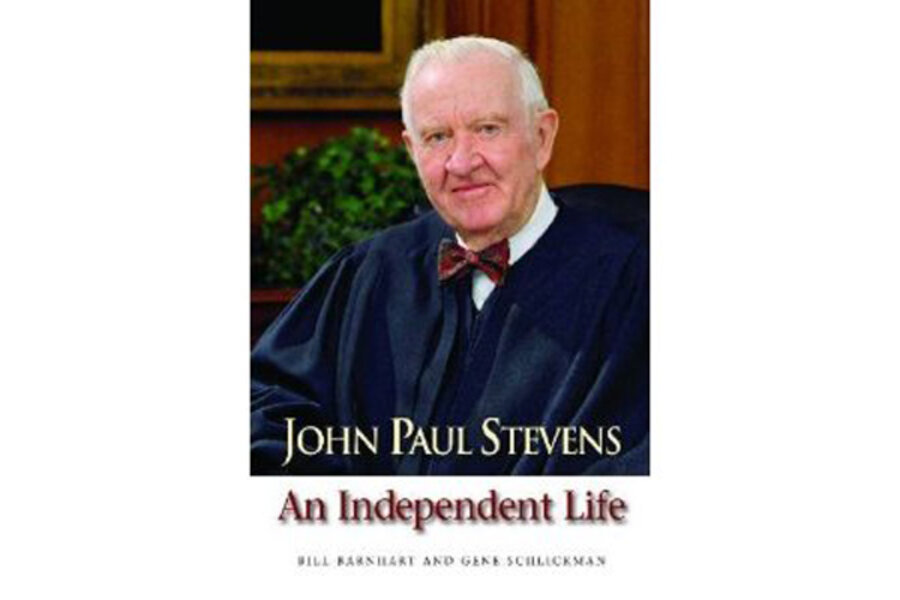

John Paul Stevens: An Independent Life

Loading...

In the weeks since he announced plans to retire from the US Supreme Court at the end of the current term, John Paul Stevens has frequently been portrayed as a throwback to a bygone era.

After 35 terms, Stevens will depart as the fourth longest-serving justice in American history, as well as the court’s sole Midwesterner, only Protestant, and last World War II veteran.

Perhaps most significantly, on a court where all eight of his colleagues vote pretty much as was expected at the time of their appointments, Stevens is also the last enigma. How did this bow-tie-clad moderate appointed by Republican President Gerald Ford come to anchor the court’s liberal wing?

Bill Barnhart and Gene Schlickman set out to answer that question in John Paul Stevens: An Independent Life. That title pretty much sums up their theory and governing principle: that he exhibited the same independence as a justice that he did earlier in life. But by devoting roughly two-thirds of the narrative to Stevens’s precourt life, his tenure as a justice winds up getting short shrift.

To be sure, Stevens has witnessed a remarkably long span of American history. He was born to one of Chicago’s wealthiest families, and watched their hotel fortune vanish during the Great Depression. He served as an Army code breaker during World War II, an experience which seemed to fuel his passionate dissent from the court’s 1989 decision striking down a law banning flag burning.

But Stevens’s career as an antitrust lawyer and federal appellate judge does not make for reading as interesting as the biographies of others who have served on the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren, a three-term California governor, or Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who had been a pioneering women’s rights lawyer, would have both merited biographies even if they had never become justices.

Stevens’s early life and career matter only to the extent they inform his tenure as a justice. And try as hard as Barnhart and Schlickman might to shoehorn his life into the narrative of an independent-minded maverick, it ends up feeling forced.

The authors do reveal some interesting biographical details. Stevens’s father was arrested on charges of fraud related to the family business in 1933, and two weeks later armed robbers burst into the family’s home. A jury later convicted his father, though the verdict was ultimately overturned by the Illinois Supreme Court. How much of a formative experience these episodes were on this future appellate judge is left largely unexplored.

Barnhart, a former Chicago Tribune journalist, and Schlickman, a retired Illinois lawyer and state legislator, who previously collaborated on a biography of Governor Otto Kerner, appear more fascinated by Stevens’s experiences in their home state than his tenure on the nation’s highest court.

The 19 justices Stevens served alongside are largely undeveloped characters. The presentation of Stevens’s Supreme Court tenure is confusing, presented neither in chronological order nor by area of law, either of which might have helped explain how his jurisprudence, approach to the job, or relationships with colleagues stayed static or evolved over time.

Perhaps Stevens’s tenure does not fit a neat narrative arc, and he is not easily reduced to any facile label. But it would help if the descriptions of Stevens as an idiosyncratic dissenter, pragmatic liberal, and crafty strategist were better tied together.

Some of the questions Barnhart and Schlickman raise regarding Stevens’s personal life also cry out for greater explanation. Despite all the focus on Stevens’s status as the court’s only Protestant, they give little attention to his religious observance, leaving the impression that it is not an important part of his life.

The authors also seem to suggest that Stevens had an affair with his neighbor, whom he married soon after divorcing his first wife. The oblique treatment of the issue – relying on a quote from Stevens’s daughter, who said that “there was a thing going on with a neighbor” – is perhaps admirably discreet. But having raised the question they owed readers a more complete explanation.

The end of the book reads less like a biography than a polemic on why judicial independence matters in which the authors cast Stevens as some sort of platonic ideal for future justices. Could the court benefit from more justices like Stevens as the authors want us to believe? It would be easier to answer that question if they had helped us better understand exactly who Stevens is and what he has accomplished as a justice.

Seth Stern is a legal affairs reporter at Congressional Quarterly and co-author of “Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion,” a biography being published in October by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.