Country Driving

Loading...

At a tourist spot in Beijing in the 1980s, Chinese used to line up to have their photos taken standing next to a car. In those days, most Chinese had never even ridden in an automobile, let alone dreamed of owning one. Today, new cars and new drivers are pouring onto China’s new roads at a breathtaking pace.

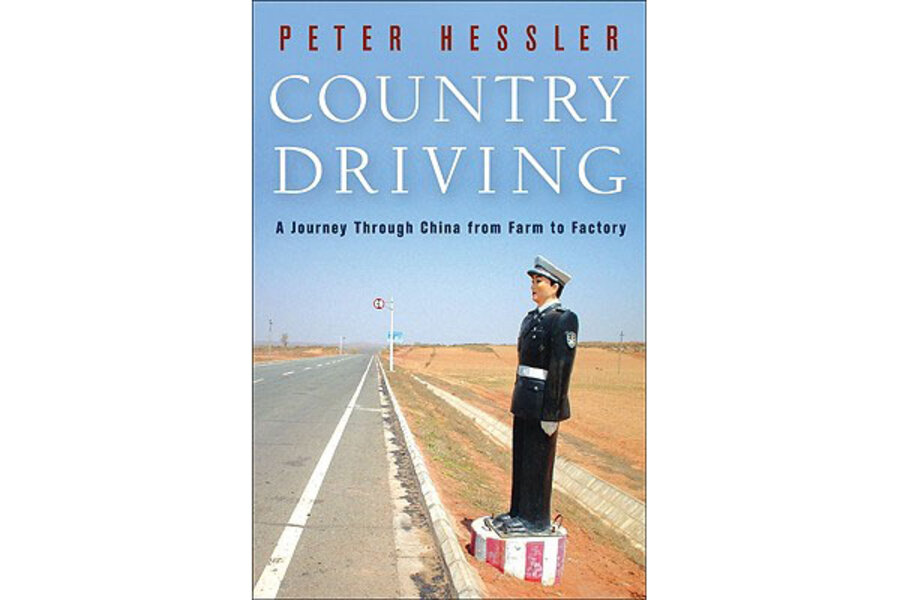

Peter Hessler, who covered China for The New Yorker, spent much of the past decade exploring the effects that this is having on that nation. In Country Driving, his third book on China, Hessler takes a road trip across China, following the Great Wall.

When not on the road, Hessler is living in a village north of Beijing, or watching a factory town spring up in southern China – the result of a new road being built in the area.

China’s automotive era is still in its early stages. In 2001, the year Hessler got his Chinese driver’s license, China had only one vehicle for every 128 of its citizens – the same ratio that the United States had in 1911.

But the country’s love affair with the car is growing rapidly – and not always comfortably. Hessler’s description of China’s new drivers is

hilarious – and frightening. He visits a driving school where students must first learn how to open and close a car door and where beer is consumed during the lunch break. Hessler notes that, with about one-fifth the number of vehicles as the US, China has twice the annual number of traffic fatalities.

“Country Driving” is sprinkled with Hessler’s humorous encounters with a state-owned car rental company. The rental agent insists that he return the vehicle with exactly the amount of gas he starts with (sending out a car with a full tank of gas “would never work here,” the agent explains). Yet that same manager is unconcerned that Hessler broke the “Beijing-only” clause and took the car on a wild journey through Inner Mongolia and other remote provinces. At the time of the trip, Hessler was also breaking a law that required foreign reporters to get permission for such trips. He managed to avoid authorities, at least for awhile, by camping out or staying in truckers’ dorms.

Light-years away from the glitzy hotels and restaurants of Shanghai and Beijing, Hessler wanders into small, isolated towns where young people have left for work in the big cities, leaving only the elderly and their grandchildren. We hear a lot nowadays about China’s economic success, but Hessler reminds us that it is still a poor country where farmers earn a few hundred dollars a year on half-acre plots and job applicants falsify their documents to win coveted factory spots that pay 40 cents an hour.

We see how Hessler’s village neighbors are dismissed as country bumpkins by city folk, and how the gap between prosperous cities and poor rural areas is widening.

“Country Driving” tells us much about contemporary China even when Hessler is not on the road. His long-term stay in that northern village gives him a rare opportunity to observe the intricacies of local politics and corruption.

When he first moves there, the roads are unpaved and there are no businesses. Later, China’s massive road-building campaign and the dramatic increase in car ownership in Beijing bring Chinese tourists to the area. Villagers seize the opportunity to earn money by running country-style restaurants. But prosperity also brings work-related stress.

Hessler has an eye for the small details that show the villagers’ way of thinking. When his neighbors allow Hessler to take their son sightseeing in Beijing, Hessler is surprised that the boy’s mother doesn’t pack him a toothbrush, let alone a change of clothes.

But the boy’s mother doesn’t see the necessity. “He’s only going for three days,” she explains. Hessler’s comment to readers: “American parents fill minivans whenever a child travels five blocks.”

In the third portion of the book, the term “boom town” takes on a literal meaning as construction crews use dynamite to flatten mountains to make way for buildings. Like a speeded-up scene from time-lapse photography, a road, factories, and workers appear in a matter of months.

Hessler is allowed to sit in on the hiring process for one factory, where a boss openly states that poorly educated girls who aren’t good looking make the most docile employees. Most workers want to earn as much money as possible in the shortest period of time. Factories that boast of overtime work and few days off are the most attractive, Hessler explains.

It’s just one of the insights presented in “Country Driving” – a fascinating road trip through a land in transition.

Mike Revzin has worked as a journalist in China, and now runs ChinaSeminars.com.