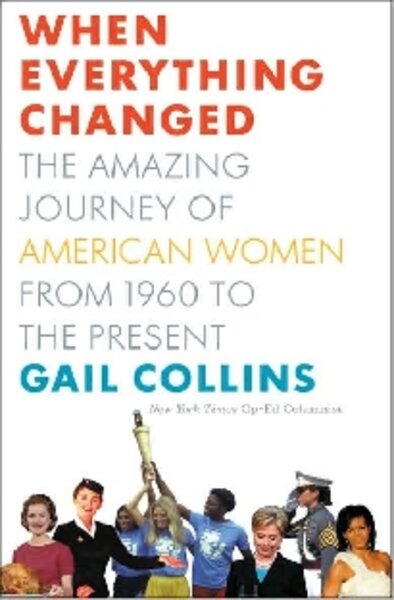

When Everything Changed

Loading...

In a year in which audiences have been captivated by Mad Men’s exploration of the early 1960s and Julia Child’s foray into the male-dominated world of Le Cordon Bleu, it seems Americans can’t get enough of postwar culture and its constraints, especially as they apply to gender. What better time, then, to look at American women’s progress since the ’60s, now that the dust has settled on the 2008 presidential election when so much was won (and lost) by women?

Women have traveled a remarkable road from the days when Lois Rabinowitz was scolded and sent home by a New York judge for wearing pants to pay her boss’s traffic ticket at a hearing in 1960. This story opens and sets the tone for Gail Collins’ near epic history When Everything Changed: The Amazing Journey of American Women from 1960 to the Present.

The question of pants, who can wear them and what they represent, is a motif that runs throughout the book.

Collins tells of female fighter pilots who were arrested for wearing slacks in Georgia during World War II; of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s rejection for a clerkship with Felix Frankfurter, who asked, “Does she wear skirts? I can’t stand girls in pants;” and more wryly, of Nixon’s comment to wire service reporter Helen Thomas at a bill signing, “Every time I see girls in slacks it reminds me of China.”

A New York Times columnist and former editor, Collins weaves together anecdotes from the lives of everyday women, as well as famous ones, to paint a picture of the period. From the Harvard dinner where the few female students, including Ginsburg, were asked why they were taking spots from men, to Betty Friedan’s ejection from the bar of the Ritz-Carleton (she was ushered off to drink her whiskey sour by the women’s restroom) women were riding the back of the bus, socially and professionally.

Yet these incidents pale in comparison to the open hostility many lesser-known women faced in the workplace, the schoolroom, and the courtroom.

Take Laura Kelber, one of the first women electricians, who, when she told her boss she was pregnant, “was immediately transferred from a relatively light indoor assignment to a different site where the job involved heavy lifting, working in the cold and no clean bathrooms.” Kelber stayed on the job, but miscarried. Back at Harvard, female law students were ignored by their professors who refused to call on them, resenting their presence in the classroom. In more recent days, studies report American women in the military are more likely to be raped by a fellow soldier than killed in combat in Iraq.

Important victories have been won in the history of women’s rights, but, Collins reminds us, often at great personal cost to women on the front lines.

Collins gives an extensive account of women’s crucial role in the Civil Rights movement; the creation and defeat of the ERA; the passage of Title IX; and the defeat of the Child Development Act, a bipartisan bill to provide federally subsidized day care that Nixon denounced as “communal approaches to child-rearing” and vetoed.

She also sheds light on the culture wars that led to a polarized debate around abortion and gay rights. In a sweeping narrative featuring women – both famous and anonymous – striving for increased rights, Phyllis Schlafly appears as a sort of arch-enemy, along with her counterpart in the gay rights movement, Anita Bryant.

Yet Collins also captures the playfulness and humor in women’s advancement through The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Billie Jean King’s defeat of Bobby Riggs (she notes its “cheesiness”), and Nora Ephron’s witticisms, which pepper the book. It’s an important reminder of the wit and success that has also marked American women’s strides forward.

Since Collins’s history concludes in the present, it’s a bit surprising that no mention is made of 9/11’s effect on the national and global discourse on women. Nonetheless, the political and social history of “When Everything Changed” make for important reading, especially for generations who can’t imagine needing a husband’s signature to obtain a mortgage or car loan.

The closing chapter circles back to pants, which a modern-day New York bus driver refused to wear, due to her religion, which in turn, led to her firing. It’s an apt metaphor for the way clothing continues to signify much more than a practical covering for women. It also signals religion’s new centrality in the on-going debates over women’s place and the extent of their freedom.

Elizabeth Toohey teaches Women’s Studies and Postwar American Literature at Principia College in Elsah, Ill.