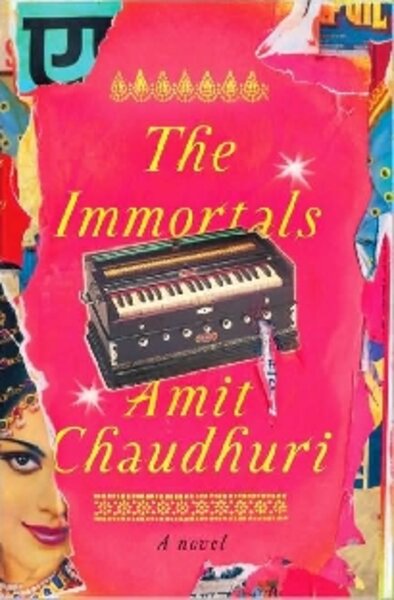

The Immortals

Loading...

The title of Amit Chaudhuri’s fifth novel, The Immortals, alludes to the legendary performers of Hindustani classical music. These include singers such as Tansen, one of the “nine jewels” of the Mughal Emperor Akbar’s court whose voice was said to be able to light fires and bring the rains, singers for whom the gods themselves would stop and listen.But Chaudhuri’s characteristically gentle new book is concerned with mortals, and the less lofty practice of art in a commercial world. Set in Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay) in the late 1970s and ’80s, where the author also grew up, the novel revolves around two families – the well-to-do Senguptas and the up-and-coming singer Shyam Lal and his extended family. Their lives are entwined by music.

Mallika Sengupta is a singer of some talent and a little ambition – but not enough to make her give up a comfortable life as the wife of the managing director of a company. Lal is her music teacher and the son of an acclaimed singer. He has the lineage and the gift but is ultimately pragmatic, content to do just what is necessary to support his family and those of his brother and sister.

The novel follows the Senguptas as they ascend the corporate ladder, moving to ever-larger apartments in the towers of south Mumbai that overlook the sea. They lead the predictable lives of the city’s elite – afternoons at the colonial-era club, evenings at business dinners or cocktail parties, or sometimes, at the concert hall. It’s no wonder their teenage son, Nirmalya, is discontented. Ill at ease with his parents’ bourgeois lives, he wanders the city wearing torn kurtas and clutching a copy of Will Durant’s “The Story of Philosophy” (a staple at Indian colleges).

But his unrest is half-baked. One day he says he wants to go to the Himalayas – shorthand for renouncing the world for a life of spiritual contemplation – the next, he’s eating “chili cheese toast” with his parents in the Sea Lounge of the Taj Hotel.

This almost absurd disjunction between ambition and reality pervades the novel. The Senguptas scale the corporate ladder, but they never become really wealthy – their lifestyle relies on expense accounts. Mallika thinks she could have been as famous as Lata and Asha, the trilling real-life sisters who rule commercial Hindi music, but she lacks the hunger needed to make it big.

Nowhere is this gap between the sublime and the mundane more evident than in the world of music. After spells with rock ’n’ roll and Sartre, Nirmalya turns to Hindustani classical music and begins singing lessons with his mother’s teacher. He’s caught up in the romance of the Indian music heritage: its ancient, seemingly ageless roots; its maestros and “gharanas” (schools of musical styles); and the way it passes from generation to generation, from guru to apprentice – that most idealized of Indian relationships, commanding an almost abject devotion from the disciple.

But Lal is no romantic ideal, fitting neither an Eastern notion of the artist as mystic nor the Western one of the artist as rebel. He’s a master of his art but also an “itinerant with his own compulsions.” He teaches whoever can pay his fees, whether they are the bored wives of diamond merchants or aspiring film stars. His livelihood depends on “the vanity that makes people sing.”

When Nirmalya criticizes him for choosing to teach and sing lighter, popular songs, Shyam replies: “You can’t sing classical on an empty stomach.”

An accomplished classical singer himself, Chaudhuri is at his evocative best in the passages on music – he describes a raga, or melody, as a living being that “comes and stands beside you.” Or when he’s writing on Mumbai, a city that eats the sea, its newly reclaimed coastline “like the edge of a young planet.”

Chaudhuri, who is also an essayist and literary critic, is something of the anti-Rushdie of Indian English literature. Where Salman Rushdie’s prose is exuberant, with novels veering perilously between the real and magical, Chaudhuri’s style is quiet and understated. His stories center on the quotidian. Epiphanies, if there are any, tend to lie in the everyday.

This also means that his novels can sometimes seem slow, even humdrum. “The Immortals” is no exception – all mood and little plot, it feels a little like one of those Mumbai afternoons before the rains: hot and heavy and unbearably still, waiting for something to break. In Chaudhuri’s novel, it never does.

Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar is a national news editor at the Monitor.