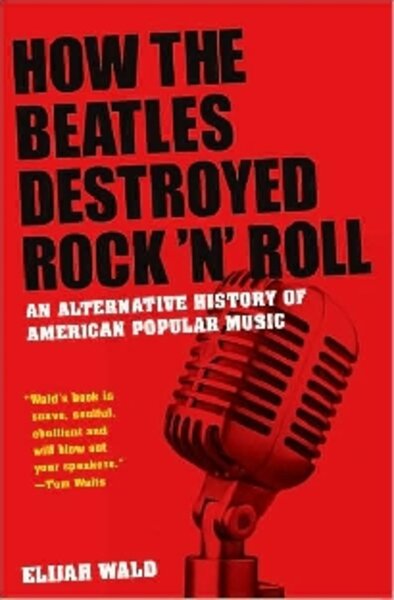

How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll

Loading...

First, the author deserves a rap on the knuckles with a ruler for this preposterous title, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll. Not only is it a shameless ploy to hook all of us Fab Four lovers into a street fight – “Hey, take it back!” – but it’s blatantly disingenuous. He doesn’t really mean it.

But a more apt title like, “How the Primal Power of Early Jazz and Rock was Diffused by the Pursuit of Artistry and the Vagaries of Gender, Race, and the Demands of the Marketplace,” might have had a tough time making the bestseller list, not to mention fitting on the spine.

Despite its incendiary title, Elijah Wald’s book is a serious treatise on the history of recorded music, sifted through his filter as musician, scholar, and fan. In the introduction, Wald lays out his premise: Though he was a Beatles fan from the instant he heard their first American LP “Meet the Beatles,” with its danceable, infectious songs blasting from the family’s hi-fi, the Beatles’s rapid development as “recording artists” (as opposed to a live rock ’n’ roll band), left him feeling somewhat abandoned.

“My much older half-brother gave my parents Sgt. Pepper. I could tell it was a masterpiece – but it was not really my music. It was adult music.... I played it occasionally, but nowhere near as often as the band’s early records. It simply wasn’t as much fun.”

From there we learn that the declarative book title stems not from the author’s own opinion, but from that of Beatle bashers “within the small world of music nuts” who fervently believe that they did, indeed, destroy rock ’n’ roll, “turning it from a vibrant black (or integrated) dance music into a vehicle for white pap and pretension.” Again and again throughout this book, Wald returns to debate the question, “Is music for dancing, or listening?” (And I keep thinking ... what’s wrong with both?)

Beginning at the turn of the 20th century, Wald chronicles the parallel development of jazz, radio, and music recording, as sheet music and a piano in every parlor gradually gave way to armoir-sized radios and the gramophone. (No shortage of piano movers in the ’20s and ’30s, apparently.) Soon the denizens of dance halls weren’t the only ones able to enjoy the popular songs and bands of the day, as listening to music at home became as much an American pastime as dancing to it.

No working band of the time could possibly crisscross the country via train enough times in a career to equal the reach of one coast-to-coast NBC radio broadcast. Radio also changed the music that dance bands played, creating a sudden demand for singers. “Instead of having to project their voices with lung power and technique (to be heard over the large orchestras), the radio crooners were murmuring to listeners in living rooms.”

Formerly only a novelty vehicle to deliver a verse or chorus in the middle of an long instrumental arrangement, band singers like Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby now found themselves literally standard-bearers, indelibly linked to the songs they crooned to millions of enraptured listeners, night after night, on the radio.

A few of the most popular “jazz” artists of the early radio days, Guy Lombardo and the Royal Canadians, and the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, get a belated turn in the spotlight to illustrate the book’s salient themes. Whiteman, a savvy musician/composer/arranger from Denver, springboarded off the popularity of early African-American jazz by incorporating its chord changes, melodies, and syncopation in a sophisticated dance orchestra setting, including a string section – and radio embraced his smooth and full-bodied sound in the 1920s. An astute judge of talent, Whiteman discovered and mentored many gifted musicians and singers during his reign as “America’s Jazz King,” including Jack Teagarden, Bix Beiderbecke, and a young Bing Crosby.

Whiteman’s legacy, in a nutshell, is the same as that of the Beatles, according to Wald. Whiteman adopted a primal, rhythmic African-American style of music, then developed his own, tamer, smoother version – which voided much of what made the source material appealing in the first place – thus alienating music critics, even as he attracted legions of happy fans.

(Although considered one of the greatest jazz innovators of all time, as well as being a fine composer and arranger, a progenitor of the WWII-era swing bands to follow, and an inspirational leader to impeachable legends like Duke Ellington, Whiteman rarely makes an appearance on any list of jazz greats, nor have many of his records been converted to CDs for modern-day fans. The man who commissioned Gershwin to compose “Rhapsody in Blue” for his orchestra is, today, hardly a blip on the radar.)

Wald points out that for every genuine talent that appeared on the scene like Elvis Presley, a batch of wholesome, less threatening surrogates were trotted out like Pat Boone, Ricky Nelson, and Fabian – all selling millions of records. Perry Como and Connie Francis were huge recording and TV stars at a time when Little Richard, Ray Charles, and Dinah Washington were redefining American music styles, yet the black stars could not get their records played on mainstream radio.

Wald follows the segregation of white and black musicians through the 20th century, noting that the band of swing clarinetist Benny Goodman was the first major act to integrate in 1935. “Goodman’s breakthrough led to a new level of acclaim for black players and bands, just as Elvis Presley’s success would do wonders for the careers of Chuck Berry and Little Richard, but white artists and aggregations that sounded sufficiently black could almost always get better jobs and more money than their African-American counterparts.”

Race is a consistent theme throughout this book, weaving its way through the decades and musical styles. Of course, its influence cannot be separated from any serious discussion of American history, especially music. As the split between music for dancing and music for listening grew, notes the author, it further divided and defined black and white musical styles. “The segregation of American popular music that began with the British Invasion has hurt white music more than it hurt black.... [M]eanwhile black dance music of the 70s led into hip-hop and rap, which have inspired and transformed popular styles around the world.”

The subtitle of Wald’s book is “An Alternative History of American Popular Music.” It’s a brave and original work that certainly delivers on that promise, though the author seems at times as conflicted about the value of certain artists and forms of music as were the timid radio programmers and record company executives back in the day.

In my view, music, like any art form, is best experienced without preconception. The guileless reaction of the listener would seem vital to the efficacy of the musical expression. Wald’s attempts to explain every nuance of how we react to music sometimes comes off like the diagramming of a joke. After a while, it’s just not funny anymore. I often felt myself wanting to put the book down so I could just enjoy some music without thinking about it.

Oh, and about that title.... As it turns out, Wald really loves the Beatles. But he hates them for selling out to arty pretension. He just wishes they had never progressed. On the other hand....

John Kehe is the Monitor’s design director, occasional music critic, and resident Beatles fanatic.