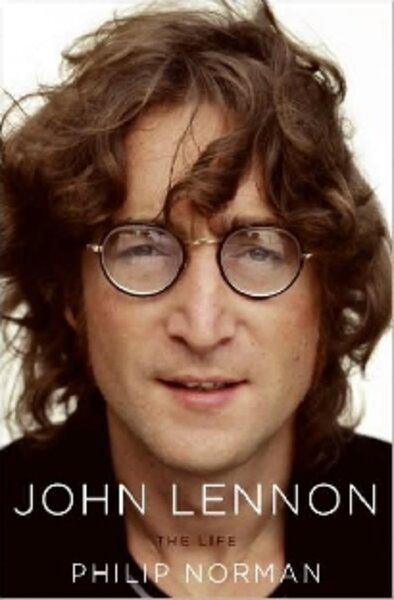

John Lennon: The Life

Loading...

“You see, part of me is a monk and part of me is a performing flea,” explains John in Philip Norman’s splendid biography John Lennon: The Life. But the duality doesn’t end with that of quiet intellect/rowdy rock’ n’ roller.

Norman shows John to be as maddeningly cruel as he was disarmingly gentle, as competitive as he was philanthropic, as materialistic as he was eager to find answers to life’s deeper questions.

In short, John Lennon’s life was as inspired and messy as was the 1960s, that transforming decade in which he reigned as rock star, fashion initiator, and anthemic voice of the counterculture.

Norman faces the challenge of Lennon’s incongruities by taking it slow, and long – at 851 pages this is no weekend romp of a book.

Yet, its ambitious range proves to be its strength, enveloping you in ways that a quicker read could not. Norman’s spry prose never wanders into dusty Beatle ephemera or the false thrills of a tell-all.

At once retrospective and immediate, the author pulls us through time with luminous detail, wisely resisting the temptation to psychoanalyze Lennon from afar.

The result is a wonderful unfolding of Lennon’s life with all its talent, tenderness and tragedy.

Much (or should I say MUCH) has been written about the Beatles, and although Norman brings new clarity to that most famous period of Lennon’s life, where this book really intrigues is in its three-dimensional portrait of the rocker’s youth, and in its patient piecing together of John’s years with Yoko Ono.

The story of the boy Lennon reveals our subject as the rebel you want to root for, the Liverpool lad who, for all his wit and brilliance, just can’t get with the curriculum. Unlike some Beatle bios that include the obligatory “Early Years” chapter, here John and Paul McCartney’s suburban Woolton springs to life.

Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields are given the backstory they deserve, and counting the references that make their way into later Lennon/McCartney songs is downright fun. Under these blue suburban skies where English propriety tussles with a seaport’s vices, young John doesn’t always meet with our approval, but he has our empathy from the start.

Norman provides a satisfying explanation as to why Lennon’s care was turned over to his Aunt Mimi. Tender and turbulent, it’s in this relationship with Mimi that we witness John’s affectionate side and hold out hope for the sexually active, cheeky teen with a penchant for shoplifting.

As the book shifts into the Beatle years the pace (and our pulse) quickens, and we’re entertained with all the thrills and spills of the Fab Four’s rise to acclaim: their fanatical following in Liverpool; their Hamburg exploits; their shock at the sudden death of bassist Stuart Sutcliff, John’s closest friend; their fortuitous teaming with producer George Martin; their love of Ringo and his inevitable addition to the band; their astonishing conquest of America.

The sadder side of the story

Yet, in spite of seeing the band he created succeed beyond imagination, John Lennon was a man conflicted. His songwriting began to take on a confessional, insecure tone in hits such as “Nowhere Man,” “I’m a Loser,” and “Help,” – hardly the typical mind-set of a man topping the charts in the mid-’60s.

Reading Norman’s take on the last years of The Beatles is a bit like watching the psychedelic bus from the band’s Magical Mystery Tour tumble off a cliff.

The inanity of fame, the bad business decisions, the drug-blurred reasoning, and the once-healthy artistic competitiveness of John and Paul turning as sour as the green Apple Records logo all led to the band’s never-to-be-resurrected demise. We all know the story, but it’s still sad reading these many years later.

A truer picture of Yoko

And then there is Yoko. Her very name has become synonymous with that of the meddling woman. To Ono detractors she’s a scheming, no-talent, fame-seeker who ruined John’s marriage to Cynthia and seduced him into disbanding the Beatles.

But here the cruel caricature slowly dissolves. Regardless of the fact that her provocative performance art rarely worked in collaboration with John’s pop songwriting, Norman’s impressive research, including new interviews with Yoko herself, shows her to be a novel thinker and devoted helpmate to John.

As for Cynthia and the Beatles, John’s marriage was rocky at best before meeting Yoko, and he was becoming increasingly uncomfortable with his role as “performing flea.”

Norman’s portrayal of Lennon suggests that Yoko had little to do with the breakup of the Beatles and this book should go far in helping grant her the reprieve she is owed by the public.

Which makes it all the more sad to learn that Yoko Ono has decided not to endorse this book, calling it “mean to John.” Knowing what we know of Lennon, it would not be possible to present his life with the imperfections airbrushed out. And he is hardly the only 20th-century songwriter with a troubled life.

Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Chuck Berry, and Bob Dylan all present prickly challenges to their fans, with much to love and much to forgive.

Lennon’s final years saw him rearrange his priorities to become a sober, loving, hands-on father.

Yet, contradictions remained. Has there ever been an artist who so desired celebrity, yet with a wink and a joke reminded us of the charade of it all? Despite the searing honesty of Lennon’s songs and his tell-it-like-it-is repartee with the press, much of the man has remained an enigma.

Until now. Philip Norman’s “John Lennon, The Life,” is a gift of a book, heartfelt and heart-rending.

Lorne Entress is a musician and lifelong Beatles fan.