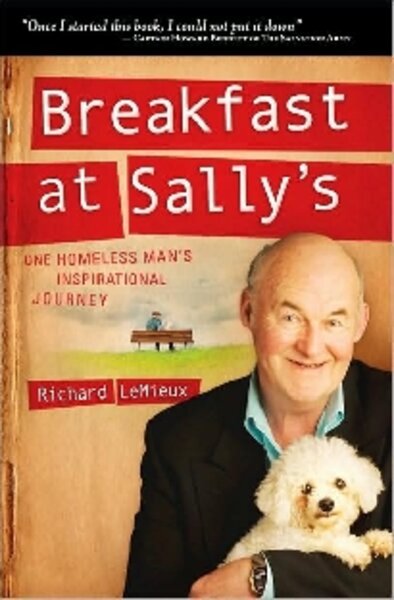

Breakfast at Sally's

Loading...

We’re all aware of them, though most often only as shadows in the backgrounds of our busy lives. Once upon a time, it was that way for Richard LeMieux as well.

"I had seen the poor before, of course,” he writes. “I had given to street people many times – a quarter here, a quarter there. As an affluent businessman, I had sent checks to the Salvation Army and the Union Gospel Mission.... I had seen [the homeless] late at night ... moving across the landscape like nomads.”

But suddenly LeMieux was given a perspective most of us will be fortunate enough never to have: He became one of them.

Once a wealthy publishing executive living in a huge beachfront home with boats, cars, and “all the toys a man would want,” at the age of 59 LeMieux saw his fortunes dramatically reverse. His business went under when the Internet rendered the directories he published obsolete and he lost everything.

Destitute and plunged into a debilitating depression, he lost his friends and family as well. (“You must feel like Job himself,” a psychiatrist told him.)

Finally, all that was left to LeMieux were a beat-up van and his small white dog, Willow. And so begins the saga that LeMieux chronicles in Breakfast at Sally’s: One Homeless Man’s Inspirational Journey.

LeMieux almost gives up right at the outset. Poised to jump off Washington’s Tacoma Narrows Bridge on Christmas night 2002, he turns back when he hears Willow barking frantically and reflects that it would be unfair to desert the one being who has stayed loyal to him. So he returns to the van and launches on what turns out to be a voyage of discovery.

He sleeps in church parking lots and accepts free meals from any charity that will offer one. (Hence the title of his book: “Sally’s” is the Salvation Army, one of LeMieux’s regular stops.)

Living and moving with the poor, LeMieux’s first discovery is how much collegiality exists among their ranks. One of his first friends is “C,” a brainy drifter with substance-abuse problems who shows LeMieux the ropes and shares generously with him, even once treating LeMieux to the opera.

As he travels with “C” through his world he encounters drunks, druggies, and people on the run from the law. He also meets (and often they are the same people) the traumatized, the frightened, and the depressed. He sees homeless families and watches parents doing their best to nurture children in that strange, twilight landscape.

Without homes or addresses, LeMieux comes to realize, all these people are “financial lepers, third-class citizens, untouchables” who cannot so much as cash checks or qualify for most jobs. “We may be the most feared and misunderstood people in America,” he thinks.

And yet, throughout it all, LeMieux also bears witness to astonishing kindness. There is the elderly woman who presses a few of her own dollars into his hand, the hospital patient who – despite her own plight – pours verbal warmth on him, the nurse who pays for him to stay in a motel, and, finally, the minister who lets him sleep in his church and encourages him to write this book.

It gets him through an ordeal that lasts a year and a half. “I get a little help here, a little help there,” he tells a fellow indigent who marvels that LeMieux, at his age, endures the rigors of such a life.

LeMieux never really offers a satisfactory explanation of how it came to be that a man once so well connected lost all his ties to society. (Particularly hard to understand is how all three of his children could have turned him away, even though he explains that depression altered him much for the worse.)

This is a lapse that to some degree harms the credibility of LeMieux’s tale, as it’s hard for a reader not to wonder if there’s some important piece of the story not being told. Also, by the book’s end, “C” has vanished without a trace, so we must take LeMieux’s word for any accounts of adventures with him.

However, despite such gaps, “Breakfast at Sally’s” has much to offer.

For those who yearn to believe in the basic decency of most human beings, this book provides abundant evidence that there are good people out there and that their efforts at well-doing are not wasted. Also, LeMieux’s story does much to humanize the homeless, reminding us that behind each of them there is a story – perhaps even an astonishing one.

Most of all, however, “Breakfast at Sally’s” is an argument for compassion. None of us can ever fully fathom the struggles of others. Nor can we begin to know how much the smallest of kind gestures might ease another’s pain.

But LeMieux’s story does remind us how essential it is to try.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s books editor.