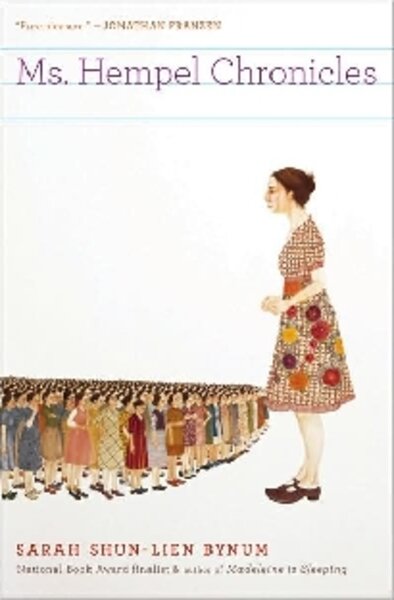

Ms. Hempel Chronicles

Loading...

Teachers, take note: You’ve got an articulate new advocate in novelist Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum. Bynum’s Ms. Hempel Chronicles is not only a warm-hearted novel-in-stories about a young 7th-grade teacher navigating the final passage to her own adulthood even as she ushers her students through the tricky narrows of adolescence; it is also a testament to how hard – and important – the work of teaching is.

In her first novel, “Madeleine Is Sleeping,” a 2004 National Book Award finalist, Bynum uses an unorthodox sequence of short, shimmering prose poems to convey a sleeping adolescent’s at-times surreally mystical dreams and fantasies. “Ms. Hempel Chronicles” is more traditional in form – eight delicately linked stories about Beatrice Hempel – but no less impressive.

Bynum is fascinated and amused by outspoken, phony-resistant teenagers in the throes of self-definition. Through her title character, she demonstrates a genuine fondness – totally lacking in condescension – for adolescents.

Why? Because these kids are “at the age when they were most purely themselves ... not yet dulled by the ordinary act of survival, not yet practiced at dissembling.”

She admires much about them, including “the efficiency with which they arrived at the truth.” They can be insecure one minute and brashly confident the next, but they’re also bursting with nascent sexuality, cynicism, and potential.

Bynum deftly introduces several of Ms. Hempel’s students through her musings during a school talent show. She captures, for example, the subtle dynamic between teacher and pupil by describing Ms. Hempel’s edge-of-her-seat engagement with exuberant, mischievous Harriet Reznik’s magic act.

Jonathan Hamish, “the toughest, craziest kid in the eighth grade,” wouldn’t be caught dead at the talent show, but he’s on Ms. Hempel’s mind anyway. Jonathan “took two different medication three times a day” and acted out frequently – once throwing a blueberry bagel at another teacher – but he’s “wearied by” his own bad behavior.

Rather than resent this disruptive troublemaker, Ms. Hempel’s heart goes out to him – in part for the way “His heart went out to the characters in the books they read.”

Much of the charm of “Ms. Hempel Chronicles” lies in Bynum’s light touch. Her portrait of the appealing young woman at its center is especially graceful. Just 10 years past her own pierced, punk-aspiring adolescence, Beatrice Hempel reflects back wistfully on her lost youth, including her oddball younger brother’s pranks and her recently deceased father’s angry outbursts.

When her chronicles begin, Ms. Hempel has been teaching at an unnamed, probably private, New York City middle school for four years. She is still unsure of her abilities and feels both drained and trapped by her job.

But she is unable to make a decision about moving on from it or from her engagement to a man whose sexual preferences make her uncomfortable.

Bynum lets us know that Ms. Hempel is too hard on herself when she questions her teaching abilities. The young teacher is popular not just because she bribes her students with miniature chocolate bars and “allowed them to use curse words in their creative writing ... [and] taught sex ed with unheard-of candor.”

Ms. Hempel wins the holy trinity of effective teaching – “attention, labor and trust” – because she shows her students she cares in numerous ways: She refuses to dumb down her vocabulary. She comes up with creative assignments designed to engage them. She inserts Tobias Wolff’s “This Boy’s Life” into the curriculum, a profanity-rife memoir of family dysfunction they can easily identify with.

Teaching is a tough job. Ms. Hempel spends hours and hours writing “anecdotals,” progress reports on her 82 students to send home to parents. In addition to talent shows, there are parent nights, sex education, Trip Days, safety assemblies, and Affinity Days to promote pride and unity among students of color.

And that’s on top of lesson plans and grading papers. Yet she’s disappointed in herself for resorting to pop quizzes, which require less time to mark than essays.

Still, Ms. Hempel worries, “Did she really teach them anything? Or was she, as she often suspected, just another line of defense in the daily eight-hour effort to contain them.”

Bynum’s take on teaching is instructive. But it’s her sensitive consideration of complex emotions and situations on the road to maturity that’s truly heartening.

Heller McAlpin, a freelance critic in New York, is a frequent Monitor contributor.