Keeping up with the Jameses

Loading...

“We were, to my sense, the blest group of us, such a company of characters and such a picture of differences ... so fused and interlocked, that each of us ... pleads for preservation.” So wrote novelist Henry James of the intense family unit into which he was born. There were four boys, a girl, and a pair of well-meaning, well-educated parents. There was money enough – and good intentions aplenty – for the children to be showered with all the best that 19th-century culture had to offer.

Yet the results were decidedly mixed. Genius did flower – at least in the case of Henry; his brother William, the pioneering psychologist and philosopher; their father, Henry Sr., an eccentric but noted theologian-philosopher; and sister Alice whose intellect shone within the family circle on a par with her famed brothers.

But all of the Jameses struggled in life with significant obstacles to personal happiness, at least some of which seemed to stem from their privileged yet stifling upbringing. Constant traveling abroad plus home schooling turned them inward to one another so intensely that William would later write that the family was the only real “country” to which any of them would ever belong.

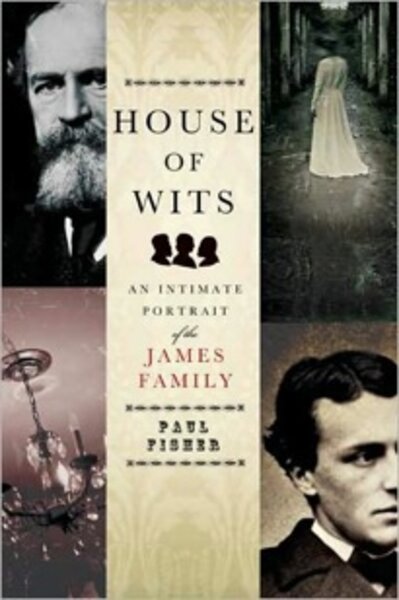

In Family of Wits, Paul Fisher takes on not only the better known Jameses, but the family as a whole is this absorbing (albeit dark) examination of the Jameses and their world.

Celebrated cameo appearances abound, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, George Eliot, Oliver Wendell Holmes, John Muir, Brigham Young, John Singer Sargent, Bret Harte, Gustave Flaubert, Ivan Turgenev, Oscar Wilde, General Sherman, Chester A. Arthur, and Edith Wharton. (And that is a very partial list. )

Fisher, who teaches American literature at Wellesley College, creates a detailed 19th-century backdrop for his characters, describing the ships on which they sailed, the rooms in which they lodged, the houses they inhabited. Yet “House of Wits” is not an examination of 19th-century culture or even the intellectual achievements of the Jameses themselves. Fisher’s focus is the family.

What he achieves is to show us the Jameses in two dimensions: how they appeared in their own time and how they seem today, in an era of a deeper (or more obsessive – take your pick) interest in familial dysfunction.

Henry Sr. came from a family made wealthy by land speculation. His wife Mary grew up in New York’s fashionable Washington Square (becoming the model for old-maid Catherine Sloper in her son’s “Washington Square”). Henry yearned for eminent offspring. He also saw European travel as the ultimate good in life.

So when it came time for his children to learn, the family traveled, exposing the young Jameses to huge doses of old-world culture and charm.

Yet they lived with both the visible and invisible scars of their father. Henry Sr. had lost a leg in an accident as a child and walked with a limp. He was also an alcoholic (although he finally quit drinking.)

His personal eccentricities were many. He was a passionate but incoherent thinker who oddly mingled radical with conservative beliefs. (He espoused free love – in theory rather than practice – yet he preached vehemently against rights for women.)

Both he and Mary devoted themselves to their children – perhaps too much. Even when Henry Jr. (or Harry, as Fisher refers to him) and William were in their 20s they still lived at home, where their parents routinely opened and read their mail.

Yet William and Harry did ultimately find their places – and glory – in the outside world. The other siblings were not as fortunate. William described sister Alice as “bottled lightning,” yet she lived crushed by both illness and the burden of what one biographer called “the enforced uselessness” of Victorian womanhood.

The two other brothers, Wilkie and Bob, truly received the short end of the stick. Judged less brilliant by their father, they were sent to the Midwest to work as railway clerks – lives for which their rarefied Jamesian upbringing left them ill-suited in the extreme.

But the siblings remained devoted to one another throughout their lives, and for all the darkness there is enduring love woven throughout the story of the Jameses.

And in the end Henry Sr. may well have considered himself a success as a parent. His very last words (although omitting his only daughter) were tenderly paternal. “Oh, I have such good boys,” he was heard to murmur. “Such good boys!”

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor. Send comments to kehem@csps.com.