A time when politicians were heroes

Loading...

Is there a more gooily satisfying read for a political junky than an insider tell-all? What could be more enticing than an opportunity to read the stains on the dirty laundry like tea leaves for validation of a pet theory?

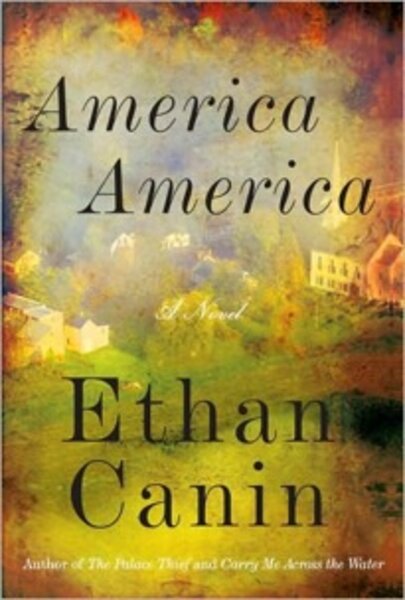

If former White House press secretary Scott McLellan’s memoir offers too much in the way of backstabbing, try Ethan Canin’s new novel America America. It’s intelligently observed, elegantly written, and no real politicians were harmed in the making of this book.

In 2006, a small-town newspaper publisher attends the state funeral of former senator and one-time presidential candidate Henry Bonwiller. Corey Sifter, however, isn’t there to cover the funeral, but to say goodbye to the lost hopes of an era.

Of course, “In towns like this, there’s always plenty to miss about the old times,” Corey says, playing down the loss. “In any case, I’m at the age when a wistful melancholy is a rather pleasant way to spend an afternoon.”

In 1971, when Senator Bonwiller seemed the best chance to unseat President Nixon, Sifter was a teenager working odd jobs on the estate of Liam Metarey, wealthy scion of a robber baron and a man determined to send Bonwiller to the White House. Eventually Corey becomes a campaign aide, sometime driver for Bonwiller, and naive witness to the crime that causes both men’s downfall. “It might seem quaint today that a whole town thought of these men the way we did then – as benefactors and guardians, and, even, if needed, as saviors. But that was what the town of Saline was like when I was growing up.”

Canin (“Carry Me Across the Water”) jumps back and forth through the decades faster than the hero of “The Time Traveler’s Wife” as the now middle-aged Corey reflects back on how the Metareys, especially Liam, dazzled him with their largesse (first giving him a job, then paying for him to attend a prestigious private school). He would have done any job Metarey asked and it’s not until he’s an adult that he understands his part “in something unforgivable.”

Liam Metarey, with his benevolent stewardship of the town of Saline and reverence for hard work, is a 19th-century throwback trying to master politics two years before Watergate. His wife, June, is a barnstorming pilot trapped in the role of a society matron. The Metarays have two daughters at school with Corey, the caustic Clara and the unstable Christian, and one older son. Watching worriedly from the sidelines are Corey’s parents and his father’s best friend.

“My loss on [my daughter’s] wedding day was simply that we had traveled so far in the world that I was now ready to give her away without tears,” the adult Corey ponders when recalling his first trip to boarding school. “I can only imagine what my parents were feeling as they readied me to go away to a place neither of them could have begun to imagine, or understand.”

Bonwiller, however, remains largely a cipher – a glowing one, we’re told, with “a voice like a cello,” but a cipher nonetheless. Corey and Liam say he was a great man who fought for workers and the environment, but we never see any of it firsthand. As a result, his disgrace feels too much like politics as usual for a reader to do much more than shrug. (It doesn’t help that Canin portrays Bonwiller as Kennedyesque in both the good and bad senses of that term.) And Canin sets up one of his characters for a big reveal, and then fails to push the button on that subplot.

But if characters on occasion prove difficult to pin down, Canin has no difficulties with his time and setting, and the strength of those details steep this novel in luminescent clarity. Take Corey’s shopping trip to Brownlee’s to buy clothes for boarding school (two cotton shirts, two pairs of pants, and one pair of loafers).

“Now, of course, Brownlee’s is long gone,” Corey reflects. “Like everything else around here, it’s been upgraded…. These days you can buy a green-tea chai downstairs, and if you prefer your Lake Erie sweatshirt to be made of organic cotton, that’s not a problem, either. But in my childhood, for my family, Brownlee’s was a very fancy place.”

“America America” is much more than a novel about politics. It’s both a coming-of-age story and a melancholy look back at a small town and a time when cynicism about politicians and journalists hadn’t yet become accepted shorthand. It’s a perfect story for an election year, but one that will be read long after November.

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.