Sedaris riffs on family, fumbles, fears

Loading...

Voice is paramount in first-person essays. David Sedaris’s slightly whiny, satirical twang and self-deprecating persona have become familiar and beloved, not just from his books – of which some 7 million copies are in print – but from his radio broadcasts and lecture tours, which fill concert arenas. By now, we hear his inflections when reading his favorite interjections, “I mean, really,” or “Come on."

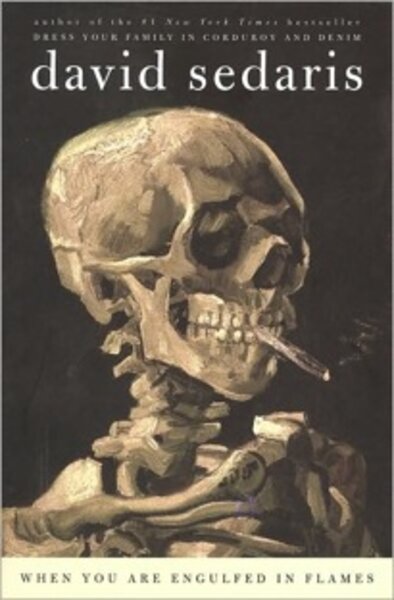

Readers looking forward to new installments of Sedaris’s endearingly eccentric chronicles will not be disappointed by When You Are Engulfed in Flames, his latest collection of 22 humorous personal essays, (although many have appeared previously in The New Yorker or elsewhere).

We all have our favorite character – whether it’s his sensitive, fear-mongering older sister, Lisa, who pushes grocery carts with her forearms to avoid germs; his wacky comedienne younger sister, Amy; or his impossibly capable, saintly boyfriend, Hugh, without whom he says he’d be totally lost.

Then, of course, there’s Sedaris himself – or at least the Sedaris he chooses to present to us: the asocial guy who strikes up friendships with outcast neighbors, the bumbler who can’t operate a car or computer, or the compulsive diarist who records his sisters’ confidences in a pocket notebook along with offbeat observations, which he then turns into profoundly funny, well-crafted stories that somehow, magically, bring home a major point about fidelity or guilt or love.

It’s all here again, yet none of it feels repetitive. Sedaris’s sixth collection follows “Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim” (2004), which was wildly popular despite what his publisher called a “willfully obtuse” title. That book contained “Repeat After Me,” which brilliantly captures the sticky aspects of milking your intimates for material and should be required reading for aspiring writers.

"When You Are Engulfed in Flames” gets its title from a booklet with tips for “Disaster Damage Prevention” that Sedaris found in a Hiroshima hotel room when he moved to Japan for three months to quit smoking.

For the most part, Sedaris finds his material close at hand – whether in the next airplane seat, a taxi, or banging against the window of his Normandy study. An essay about spiders evokes E.B. White’s “Charlotte’s Web” and his bulletins from Maine about creatures great and small. Sedaris’s focus, however, tends toward the absurdities crawling just beneath the surface of everyday life.

Sedaris, the linguistically challenged expatriate, makes a reappearance in “The Waiting Room,” which tells about the time, early in his struggles with French, when he misinterpreted a nurse’s instructions and found himself sitting in his undies in a Parisian doctor’s waiting room amidst fully clothed patients. This handicap doesn’t stop him from tackling Japanese during his three-month sojourn in Tokyo, a change of routine aimed at helping him break a 30-year smoking habit. It provides fresh material aplenty for the longest piece, “The Smoking Section,” which is destined to become a quit-lit (or quitterature) classic.

The draw, as always, is Sedaris’s utter lack of sanctimony and his use of humor as a portal to deeper feelings. Instead of insufferably touting his new purity, Sedaris recalls all those nasty habits he’s overcome – alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes – with wistful fondness. His honesty is refreshing.

Heller McAlpin, a freelance critic in New York, is a frequent contributor to the Monitor’s Book section.