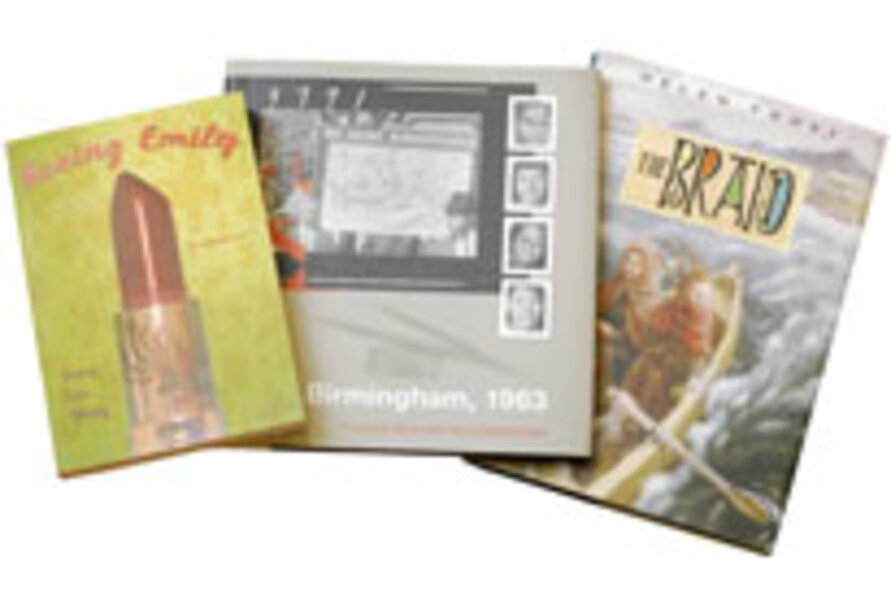

Three novels-in-verse for ‘tween’ readers

Loading...

In poetry, less is more. But don’t be fooled. Compact language hardly makes for a muted emotional impact. In fact, as three recipients of the Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award demonstrate, poetry, like coming of age, expands meanings.

And sometimes, via the most insignificant moment, it opens doors to different, deeper ways of feeling, to new modes of understanding the world.

For those who don’t run in poetry circles, a brief note about the award. Given annually by The Pennsylvania Center for the Book and Penn State University Libraries, the honor recognizes an anthology or single volume poem for children written by a living American poet.

And while there’s no bias toward free verse, several recent winners and honorees have been just that – melding poetry with a book-length narrative structure.

The 2008 award winner, Birmingham, 1963 by Carole Boston Weatherford (Wordsong, 39 pp., $19.95), relies on a picture-book format to examine a notorious day in civil rights history. Paired with archival photographs, her spare text begins with the voice of a fictional narrator, who chronicles the historymaking events of the year she turned 10.

The book may open with marches on whites-only lunch counters, but it’s the innocence of Weatherford’s details – a first sip of coffee, patent leather cha-cha heels – that sets the stage for the protagonist’s (and the reader’s) eventual horror.

The morning of the bombings begins with:

The day I turned ten…

My little brother sopped red-eye gravy

with biscuits

And yanked my pigtails like always,

Poking out his tongue when I tattled.

But when the dynamite under the church steps explodes, life (and the language that captures it) will never be ordinary again. Even birthday candles are replaced by “cinders, ash, and a wish I was still nine.”

In Helen Frost’s The Braid, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 95 pp., $16) the 2007 Honoree, history also provides the backbone for this slim novel-in-verse. In Frost’s book, though, the year is 1850, and the persecuted protagonists are not American, but Scottish.

When their family is evicted from the Western Isles, sisters Sarah and Jeannie find themselves an ocean apart with only a braid of their hair to remind them of the family they once were. But like this precious braid, their stories intertwine – each girl relating her separate, but related, stories of survival in alternating chapters.

One of the wonders of Frost’s book is the way she interweaves longer verse (chronicling the girls’ experiences) with shorter poems that capture and illuminate a small, otherwise insignificant detail. In fact, it’s often these shorter poems that both link Sarah and Jeannie and expand the story’s meaning.

For example, as Jeannie searches for building materials in Canada and Sarah’s chapter takes place “Around the rocks” in Mingulay, Frost connects the two with a poem called “Stones,” in which she imagines the seeker who:

...somehow

finds the perfect stone, exactly

the right shape and size to fit each

space in a wall.…

The way each

word comes forth and finds its way

home.

Seeing Emily (Amulet Books, 268 pp., $6.95), for which the author, Joyce Lee Wong, received The 2007 Lee

Bennett Hopkins/International Reading Association Promising New Poet Award, deals, not with history, but with a

present-day teenager’s struggles growing up within two cultures.

Emily Wu has always been a good Chinese daughter. She studies, works in her parents’ restaurant, devotes herself to her painting. But being 16 isn’t easy – even when you’re not trying to figure out where you belong.

And though Emily is terrified of disappointing her parents, she also can’t quite stop herself from experimenting with makeup – and a popular boyfriend.

Like Weatherford and Frost, Wong relies on the minutiae – on carefully chosen words, images, and metaphors – both to open new windows on the world and to pack an emotional wallop.

When Emily lies to her mother about something:

The lie sat uneasily in my stomach

like an extra piece of cake

I hadn’t been able to resist eating

even though I was already full.

More frequently, Wong chooses emblematic aspects of Chinese culture to convey Emily’s growing disconnect – and to expand the symbolic meaning of the way of life Emily can’t quite bring herself to reject.

Which is to say that “Seeing Emily,” like “Birmingham, 1963” and “The Braid,” is a rich and expansive take on a traditional coming-of-age tale. And while there’s plenty to savor in each of these award winners, it’s this beauty that springs from spareness that’s sure to leave a reader wanting more.