Bengalis replanted in American soil

Loading...

Plenty of teenagers think their parents are from another country (if not another planet), but in the case of the characters in Unaccustomed Earth, it’s inevitably true.

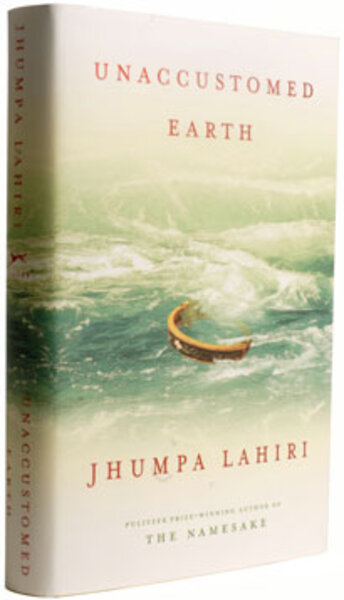

Returning to themes she explored in her first novel, “The Namesake,” Pulitzer-Prize winner Jhumpa Lahiri details with quiet precision the divide between American-born children and their Bengali parents in her new short-story collection. The characters will be immediately familiar to readers of “The Namesake” and Lahiri’s first collection of short stories, “Interpreter of Maladies”: Immigrant parents – the father typically in possession of a PhD, the mother inevitably marooned at home in a strange, freezing-cold country – raise bright, conflicted children (usually one boy and one girl) amid a generally tepid marriage.

“As a child, I always dreaded my birthdays, when a dozen girls would appear in the house, glimpsing the way we lived,” says Hema, the main character of “Once in a Lifetime.” She could be speaking for any of the young female counterparts that share the pages with her.

The children, caught between worlds, eye askance the expected journey to a prestigious college and then medicine or law, followed by marriage to the child of a Bengali friend. In one tale, there’s a running joke where a Harvard dropout gets numerous telephone calls from strange men asking her to marry them, based on the combination of her Ivy League credentials and Bengali heritage.

The most poignant stories in “Unaccustomed Earth” delve into grown children’s efforts to deal with the fact that their father’s life didn’t end when their mother died. In the title story, the collection’s best, a daughter grits her teeth, preparing for a visit from her dad, who took up globe-trotting after her mother’s unexpected death, sending her postcards from his tours.

“The postcards were the first pieces of mail Ruma had received from her father. In her 38 years he’d never had any reason to write to her.” Ruma, who is pregnant with her second child and trying to adjust to a move to Seattle, is terrified that her widowed dad wants to move in with her.

But once he arrives, it becomes clear both that he has no desire to move in and that it’s Ruma who needs him. Over the course of a week, her dad quietly bonds with his grandson and repairs the frazzled wilderness of his daughter’s backyard, while realizing, with worried pity, that she’s morphed into an early-middle-aged version of his late wife. “Ruma was now alone in this new place, overwhelmed, without friends, caring for a young child, all of it reminding him, too much, of the early years of his marriage, the years for which his wife had never forgiven him.”

When the parents disappear, the stories suffer. For example, the weakest, “Only Goodness,” is a heavy-handed examination of the guilt a sister feels for her brother’s alcoholism, and in “A Choice of Accommodations,” a couple, Amit and Megan, attend the wedding of his adolescent crush.

Most of the stories are on the longish side, and the final three linked stories are about the length of a novella. Hema’s and Kaushik’s mothers were best friends in Massachusetts, before Kaushik’s parents moved back to Bombay.

“Your mother went to a convent school and was the daughter of one of Calcutta’s most prominent lawyers,” Hema reminisces to Kaushik in the first tale. “My mother’s father was a clerk in the General Post Office, and she had neither eaten at a table nor sat on a commode before coming to America. Those differences were irrelevant in Cambridge, where they were both equally alone.”

The two meet again as teenagers when Kaushik’s family returns to the US and moves in with Hema’s parents for several weeks while they hunt for a new home. Hema is smitten; Kaushik, less so. “He was furious that we left, and now he’s furious that we’re here again,” his father jokes. “Even in Bombay we managed to raise a typical American teenager.”

In the last story, the two have a chance encounter as adults – she a professor, he a photojournalist – in Italy, at a time when both are on their way to starting new chapters in their lives.

Lahiri takes her title from a quote by Nathaniel Hawthorne, who argued that transplanting one’s roots is as necessary for the health of a family as avoiding “worn-out soil” is for vegetables. But Lahiri’s precisely rendered, elegiac tales suggest that the process is more fraught for children than it is for potatoes.