Born too late – by about 750 years

Loading...

Burt Hecker is a holy fool – or he would be if he hadn’t had the misfortune to be born 750 years or so too late. The 60-something widower is a medieval reenactor, who wanders around in a robe and sandals and refuses to consume coffee, French fries, or chocolate because they’re “OOP” – out of period.

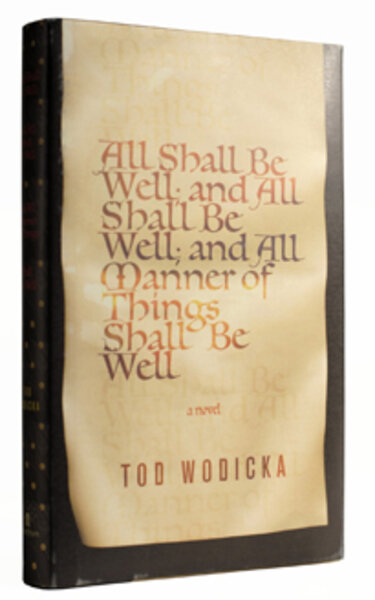

“The world is riddled with far worse activities and I altogether refuse to even feign embarrassment, especially at my age,” he announces at the beginning of Tod Wodicka’s impressively imaginative debut All Shall Be Well; and All Shall Be Well; and All Manner of Things Shall Be Well.

After a run-in involving police, a borrowed Saab, and too much mead, Burt is enrolled in a medieval music-therapy workshop in lieu of anger-management classes. The chanters, Burt included, head off to Germany on a pilgrimage to celebrate the 900th birthday of anchorite nun Hildegard von Bingen. And that’s just the first chapter.

You see, Burt isn’t ever planning on returning to the inn he and his wife own in upstate New York. Instead, he’s liquidated everything and is on a quest to reunite with his grown son, an early music prodigy he believes is in Poland studying folk music.

As Burt travels across Europe, Wodicka uses his elegantly cranky narrator to comment on everything from Frankfurt, whose “skyline looked like New York City with 80 percent of its teeth punched out,” to feminist reconstructions of history.

“Though Hildegard affirmed the lowliness of womankind and the subjugation of female sexuality, Tivona and the girls saw her as a protofeminist New Age icon, not the Catholic scold she undoubtedly was,” a bemused Burt explains about his fellow pilgrims.

In between observations, readers slowly learn how Burt came to hide away in the past and the toll his obsession has taken on his family. Among the most painful mysteries are the death of his wife and why both of his children haven’t talked to him in two years.

Wodicka’s tenderness with his oddball hero helps deepen the story from pure satire. The novel isn’t perfect: Burt’s daughter June, a newly single mom who planned to move back home with her son – not realizing that Burt had sold it out from under her – is unfairly reduced to swearing and screaming at her dad. And so much is crammed into the last chapter that the ending feels truncated.

But it’s the tenderness that stays with the reader, along with Burt’s various pearls of wisdom: “Historically, pilgrimages had been occasions for all manner of depravity, not unlike the North American tradition of ‘spring break’....” and “Shoes hamper chant.”