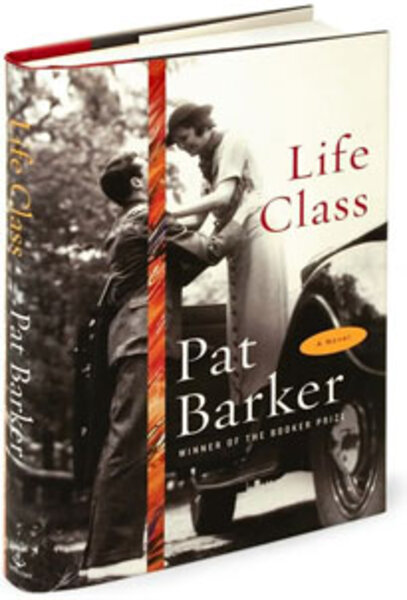

Art, love, and one giant war

Loading...

Paul Tarrant is living his dream. Thanks to a legacy from his slumlord grandmom, the 20-something from northern England is enrolled at the prestigious Slade School in London, learning to be a “real” artist. Too bad he isn’t.

Paul’s teacher, the real-life artist and surgeon Henry Tonks, offers him a devastating assessment early on in Life Class, the new novel by award-winning writer Pat Barker: Paul has ability, but nothing to say. He’s a technically accomplished void.

To make matters worse, Paul meets Kit Neville, a slightly older artist who has made a name painting the gritty, urban scenes Paul was surrounded by growing up, and which he escaped by painting pretty landscapes. To complicate things further, both men are preoccupied with the same woman, Elinor Brooke, another Slade student.

Paul, like any self-respecting artistic type, launches into a spiral of self-doubt and worry. But his existential crisis – and the love triangle – are rudely interrupted by the outbreak of World War I.

Barker, who won a Booker Prize for her World War I-set Regeneration trilogy novels, is tramping over territory she knows like her own shell-pocked backyard. But “Life Class” is very deliberately not a wartime epic. Barker avoids sweeping battle scenes and dramatic resolutions.

Declared physically unfit for the army, both Kit and Paul volunteer as Red Cross ambulance drivers in Belgium. Kit, because he’s determined to paint the battlefields; Paul, because he feels it’s the right thing to do. Once there, both get pressed into service as orderlies, and it’s Kit who finds satisfaction in the work. Paul can only endure the suffering of the wounded and the futility of much of the battlefield medical care – which Barker recounts in unsparing detail – by shutting down his emotions completely.

Meanwhile, Elinor’s response is to ignore the war resolutely and to paint only lovely things, what she terms an “iron frivolity.”

Barker doesn’t spend a whole lot of time on the joy of creating or flashes of inspiration. Instead, as she paints a portrait of how three very different personalities cope with carnage and horror, she examines the place of art in a shaken world. While Elinor feels shoved aside by a country demanding patriotism and valor, Paul finally discovers that he has something to say. In between punishing shifts at the hospital, he runs up to a rented studio to paint, so that the suffering of the soldiers won’t just be “swept away.” The irony, of course, is that once he discovers his real subject, it turns out to be too difficult for most people to look at.