The rigors of a Russian at war

Loading...

There is certainly no more commanding a subject for a book than the trials of war – particularly when these events are experienced by young idealists. Libraries and bookstores alike hold shelves of such memoirs, each one of them trying to encapsulate the horrors of armed conflict.

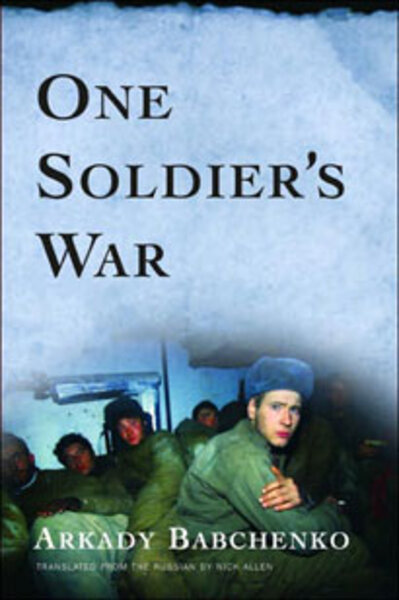

As a member of the Vietnam War generation, I have read my fair share of them. But few have ever hit me with the force and power of Arkady Babchenko’s new memoir of the conflicts in Chechnya, One Soldier’s War.

The emphasis on sociopolitical issues might incline some readers unfamiliar with the region to avoid this particular work. And that would be a shame. At the outset, Babchenko provides us with a terse and precise history of this conflict, stretching in real time from l994 to 2000. It is enough to make the journey through this book a little clearer, if not any easier.

Yet Babchenko delivers something much more than just another ghostly depiction of hell on earth. This moving narrative has the effect of transformation on a reader: You begin a young, naive, and frightened conscript and finish a hardened veteran.

In 1995, Babchenko, now a journalist, was drafted into the Russian Army at the age of 18 and sent to Chechnya. He later began writing about his 18 months of war for various Moscow newspapers. “I did not mean to write a book,” he confides early on. “I just couldn’t carry war within myself any longer. I needed to speak my mind, to squeeze the war out of my system.” The result is a set of evocative images so vibrant and at times brutal that they will stay with you, as they did with me, for days and weeks.

One of the briefest of the 27 vignettes that make up this work – the two-page tale of a dog named Sharik – is one of the most haunting.

Babchenko begins with these words: “He came to us when we had only two days of food supplies left. A handsome, smart face, fluffy coat, and a tail that curled in a circle.”

Later, Babchenko writes, “We didn’t need to reason with him, just one word and it was all clear. We warned him off and off he went. But later he came back anyway, because he wanted to be with us. It was his choice, no one forced him. Then our food started to run out.”

Sharik’s fate is clearly sealed and all I could do was to finish his story, close the book, and gasp. Being new to Babchenko’s story, one dog’s passing still had the power to wound me. And this young soldier was wounded by it, too. But it would become a minor horror in the greater scheme of things.

The system of military indoctrination called dedovshchina is stunning in its brutality. It involves the systematic beating of all young recruits approved by Russian military tradition. There is certainly nothing like it in American military life.

Should Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22” be a part of your worldview, then these depictions of Russian Army life will make it pale by comparison. Weapons are sold on the black market to the very Chechen rebels who are the targets of this struggle. Medals are given to cooks and clerks by military leaders while combat troops stand at attention, receiving none themselves. Mothers, desperate for one last encounter, search the battlefields for the bodies of their sons.

In his concluding pages, Babchenko interviews a wounded war veteran who spends his days watching the citizens of Moscow head to work on the subway. In one of the book’s most impassioned tales, this young man becomes an eloquent spokesman for all young veterans.

“I don’t understand this world. These people. Why are they alive? What for? They were given life at birth and didn’t have to pry it away from death.... But how do they spend it? Do they invent a cure for AIDS and build the world’s most beautiful bridge, or make everyone happy? No. They want to rip everyone off, stash away as much money as they can, and that’s it. So many boys died, real kids, and these people here fritter their lives away as ignorantly as a kitten playing with a ball and have no idea why they are alive.... It’s not we who are the lost generation, it’s them, those who didn’t fight, they are.”

Please allow the eloquence of this magnificent book to become part of you. You will be the better for it. I believe now that I am.