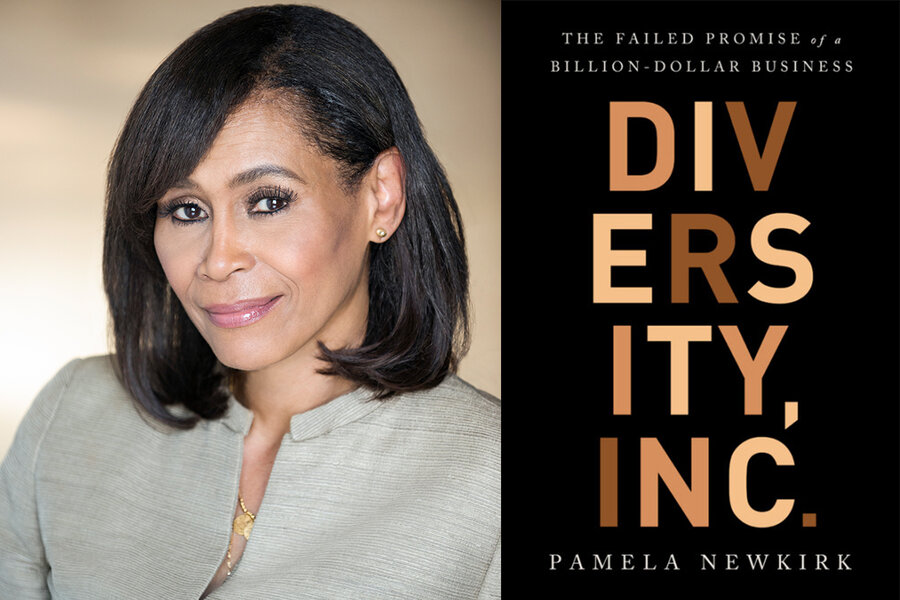

A Q&A with Pamela Newkirk, author of ‘Diversity, Inc.’

Loading...

Diversity training has become common in American workplaces. But the consultants and training sessions have made little progress toward solving racial disparities, according to Pamela Newkirk, author of “Diversity, Inc.: The Failed Promise of a Billion-Dollar Business.” She spoke with Monitor correspondent Randy Dotinga.

Q: What is the diversity-industrial complex?

It’s a huge apparatus that has grown around the whole notion of increasing diversity in the workplace: training, consultants, surveys. It’s become commonplace in institutions such as Fortune 500 companies and universities.

Q: When did this begin?

You could look to the ’70s. We were looking at equal-opportunity laws and affirmative action and trying to bring people of color into spaces that had historically excluded them. Then women were added to that category.

But in recent years, diversity has been expanded to include [other] marginalized groups, such as people with disabilities or people who are LGBTQ. The term began to overshadow the lack of diversity of people of color.

Q: What about diversity for other groups?

I’m not saying that the other marginalized communities should be overlooked. But you also have to continue to look at racial diversity because we haven’t yet bridged the gap that’s been so acute in our society from the very beginning.

Q: How have our efforts failed?

Many companies see diversity programs as a way to both show that they care about this issue and also to protect them from the legal consequences of not having diversity. But when we look at the numbers, we have not made the progress that many people assume. African Americans are still underrepresented in most influential fields – academia, journalism, architecture, fashion. We’re looking at so many different categories of diversity that we’ve lost sight of that.

Q: Why isn’t training sufficient?

You can’t begin to cure ... racism in a couple hours of a training session. Many studies have shown that mandatory training can fuel a backlash, particularly among white men who see it as punitive and humiliating. ... But if you organically tap into networks that are broader, you may find people with the skills and traits that are missing in your operation. Then you value the person not because they have a different skin color but because of what they can bring to the workplace. You can also intervene to make sure that people are treated fairly, and you can do it without training.

Q: How so?

One example is Coca-Cola, which acted following a settlement in a discrimination lawsuit that’s one of the largest of its kind in legal history. They looked at salaries, promotions, and bonuses on racial and gender lines. By monitoring those metrics, they were able to detect patterns of bias in real time that they can then disrupt. Before someone was even offered a job or awarded a bonus, they would look at the numbers to make sure that they were commensurate with other employees in the same job category. This is because they found in the discrimination lawsuit that African Americans were paid less than [other] people in the same job categories. This is a way to correct that and make sure that you have a level playing field. They were able to achieve something close to parity over a period of five years with this kind of diligent monitoring and intervention.

Q: Do you have reason to be hopeful?

There are successful models that work. If you’re a leader of an institution and you want to move the needle on this, you can replicate those models. In many ways, institutions seem to be farming out this problem to consultants and diversity czars. It’s a leadership issue, and leadership has to own it.