The ‘Voltaire of the Arabs’ is lionized in France, but imprisoned in Algeria

Loading...

| PARIS

A renowned Franco-Algerian writer’s detention in Algeria has cast in stark relief the challenges that France faces in protecting writers who criticize Islam and authoritarian governments.

The Nov. 16 arrest of Boualem Sansal, who some call “the Voltaire of the Arab people,” points to the limits of France’s leverage with its former colony, as French officials seek Mr. Sansal’s release.

France has long held up its literary tradition as a space where freedom of expression can thrive. But Mr. Sansal’s arrest has shown that its protections can only go so far, especially for Franco-Algerian writers who carry the weight of the two countries’ complex, 132-year-long colonial past.

Why We Wrote This

France’s support of free speech has made it a refuge for writers. But the country’s colonial history often stands in the way of protecting those writers from persecution by authoritarian governments.

“Five generations of Algerians have felt ignored, marginalized, and dominated by European powers,” says Alain Ruscio, a historian and specialist in French colonization. “The Algerian government uses that collective memory and pain to exert power over its people. In the case of Sansal, he may have extreme ideas, but you don’t put someone in prison for ideas.”

Mr. Sansal is best known in France for his 2015 dystopic novel, “2084: The End of the World,” a postapocalyptic, Orwellian look at a world under the control of a religious totalitarian regime. He has won several of France’s top literary prizes. He has been an open critic of Algeria’s authoritarian government.

At 80 years old and in ill-health, Mr. Sansal risks not only life imprisonment, but also becoming one of around 200 political prisoners currently held in Algeria.

The French government was quick to urge Mr. Sansal’s release (he holds dual French and Algerian citizenship), and the prestigious Académie Française considered inducting him into their ranks as a show of solidarity. But Mr. Sansal’s arrest comes at a time when Franco-Algerian relations are particularly fraught. Despite mobilization among French intellectuals, his future remains uncertain. On Dec. 11, an Algerian appeals court rejected a plea to free Mr. Sansal.

France as literary haven

Since long before Mr. Sansal’s arrest, France has served as a refuge for writers who struggled to find freedom in their home countries. American James Baldwin (“Giovanni’s Room”), Czech writer Milan Kundera (“The Unbearable Lightness of Being”) and Iranian author Marjane Satrapi (“Persepolis”) are just some of the writers who have made France their literary safe haven.

Mr. Sansal had found intellectual shelter in France, as his native Algeria (where he and his family live) became increasingly oppressive toward its literary class. His book, “2084: The End of the World,” won the prestigious Académie Française’s top prize in 2015, and he has been a mainstay on the French literary conference circuit.

“Algeria has seen its literary space narrow enormously or completely removed. There is no room for freedom of expression,” says Mounira Chatti, a professor of Francophone and post-colonial literature at the Université Bordeaux, Montaigne. “Meanwhile, this space is always open and available in France. Boualem Sansal represents this fantasy of the grand intellectual figure.”

But Mr. Sansal has long used his pen as a sword, criticizing Algeria’s authoritarian leadership, radical Islam, and religious ideology.

In France, his critique of Islam and Israel have pegged him as Islamophobic and anti-Zionist among some left-wing intellectuals, who say his political views veer toward those of Marine Le Pen and the far right.

In October, during an interview with French right-wing media Frontières, Mr. Sansal declared that Western Algeria was part of Morocco during the French colonial era, casting doubt over the borders of Algerian territory.

Later that month, French President Emmanuel Macron affirmed his support for the Western Sahara to be under Moroccan sovereignty. The territory is currently partly controlled by the Algerian-backed Polisario Front and has been at the heart of a decades-long dispute.

Mr. Macron’s comments put a strain on already tense relations between France and Algeria, which are still recovering from Algeria’s cutting of diplomatic ties with France in 2021. That has made Mr. Sansal, who touched down on Algerian soil in November, the perfect target, says longtime friend Xavier Driencourt, a former French ambassador to Algeria.

“Boualem Sansal writes and publishes in French, has French nationality, and is critical of his home country,” says Mr. Driencourt. For some Algerians, “Sansal is seen as participating in a conspiracy between France, Morocco, and Israel against Algeria.”

So, even if France may have a vested interest in defending Mr. Sansal, observers say any outward intervention could backfire.

“France should defend its citizen, of course, but it must do so discreetly and perhaps by way of an intermediary, like Germany, Switzerland, or Qatar,” says Bruno Péquignot, a sociologist and professor emeritus of arts and culture at the Sorbonne Nouvelle University in Paris. “If France defends Sansal too explicitly, it’s more proof to Algeria that he’s a traitor.”

Criticism from the left and right

Mr. Sansal’s extreme views about Islam have cost him support not only in Algeria but also in France. Several French commentators have justified his arrest based on his political beliefs, and while outspoken Green party MP Sandrine Rousseau denounced his imprisonment, she has also said that Mr. Sansal is “not an angel.”

This double standard has frustrated members of France’s Franco-Algerian literary circle. Kamel Daoud, Mr. Sansal’s friend and the first Algerian to win France’s prestigious 2024 Prix Goncourt for “Houris,” told French radio in early December, “if you talk about Islam, you’re Islamophobic. If you criticize your home country, you’re against migration. In Algeria, we’re accused of being too French and in France, we’re not ‘good Arabs.’”

Mr. Daoud has also clashed with the Algerian government, which has accused him of stealing the personal story of a patient of his psychiatrist wife for “Houris.”

Still, France’s literary and intellectual community – despite being largely left-wing – has rallied in support of Mr. Sansal. His publisher, Éditions Gallimard, launched a crowdsourcing fundraiser on Dec. 2 for his legal fees, and some 30 French writers who have won the Académie Française’s Grand Prix for fiction published an open letter calling for his release.

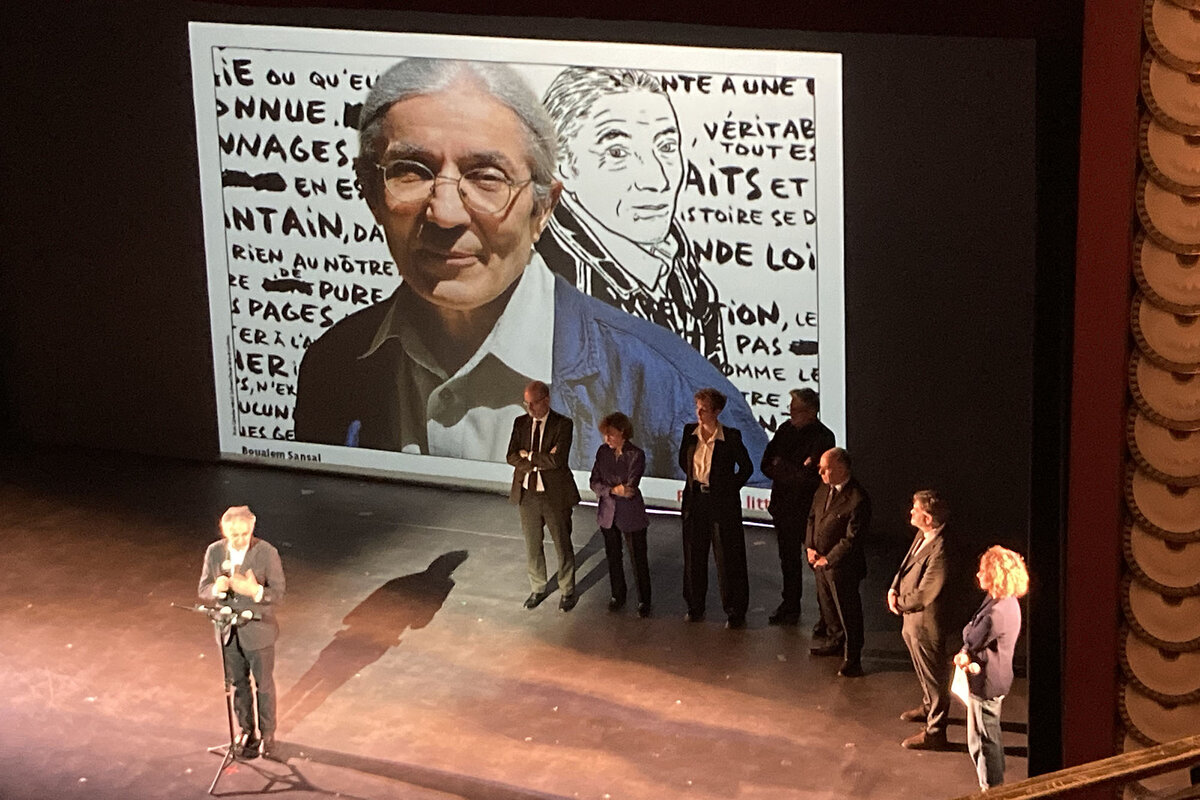

On Dec. 16, a 700-member committee created in Mr. Sansal’s honor organized a special event to remind the public of the importance of freedom of expression – a highly-prized French value. Organizers said the biggest risk for Mr. Sansal now is that his case will slide into the realm of indifference.

“The message I want to send Boualem Sansal is: We don’t know how long this nightmare will last,” said François Zimeray, Mr Sansal’s lawyer, to a packed theater of the writer’s supporters. “But until he gets out, we’ll be by his side.”