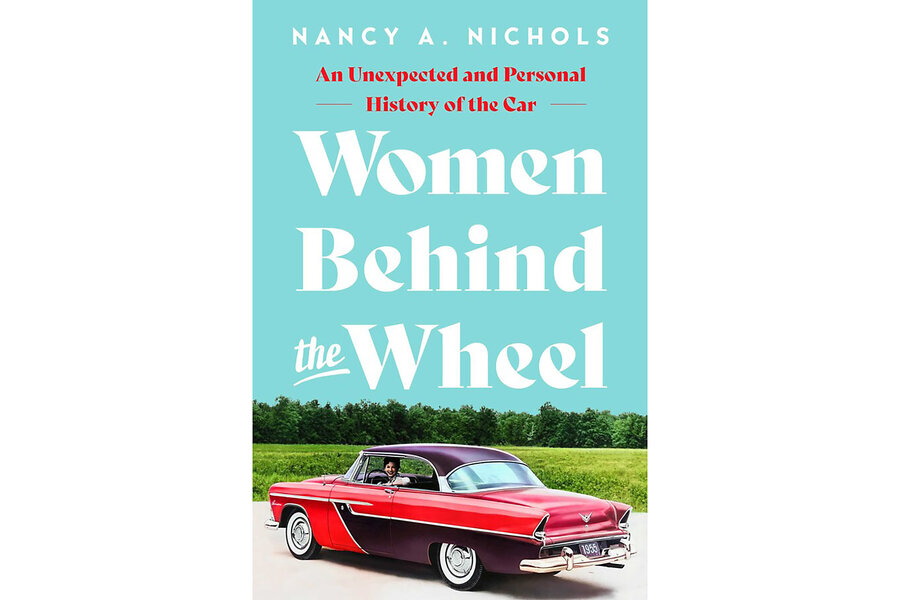

‘Women Behind the Wheel’ punctures the idea that driving meant freedom

Loading...

Cars loomed large in Nancy Nichols’ childhood. She grew up in the 1960s and ’70s in Waukegan, Illinois, the daughter of a used-car salesman who apparently fit the worst stereotypes associated with his profession.

“My father lied about everything, consistently, reflexively, whether his lies served a purpose or not,” Nichols recalls in “Women Behind the Wheel: An Unexpected and Personal History of the Car.” The book is a spirited exploration of the effects of the automobile on American women. It’s grounded in historical research and cultural analysis, but the journalist’s own life story drives the narrative.

The author’s parents separated when Nichols was 5, and her mother died a few years later. From that time on, she lived alone with her unstable father, in a house whose lawn was littered with cars in various states of disrepair and whose furniture was piled with spare parts. Getting a driver’s license allowed her to escape a chaotic home life. “Is it an overstatement to say I didn’t come alive again until I could drive?” she muses. “Probably, but that’s how I remember it.”

With freedom came responsibility. As a driver, Nichols was obligated to run errands and to get a job to help support her small household. Despite the fact that she was only a teenager, she sees her experience as consistent with a broader pattern. While women were deemed unfit to drive when the car was invented, once they were handed the keys, the expectation was that they would “use their automobiles in the service of family.”

Men, Nichols argues, haven’t faced the same imperatives. “For men the car has always symbolized adventure and escapism,” she writes, “but for women the car likely means a longer to-do list.” The suburbs, she observes, wouldn’t exist without the automobile. And women’s lives there have often revolved around food shopping and driving their children to and from school and after-school activities.

The types of cars marketed to women have tended to reinforce their domestic roles: Over the decades, the station wagon and the minivan have been touted for their ease in accommodating children and groceries. Nichols points out, however, that automakers avoid associating any of their products too strongly with female drivers. “There is an old adage in Detroit that a woman will buy a man’s car, but in no instance will a man buy a woman’s car,” she notes.

“Women Behind the Wheel” is written with a breezy tone that mostly works. It’s also timely, as electric and autonomous vehicles are set to bring about great change. Nichols ponders privacy concerns likely to emerge “when your car is essentially one big app sending data to unknown parties about your whereabouts and habits.” And she worries about the ways this surveillance might affect women, citing, as examples, data revealing an illegal trip across state lines to an abortion clinic or an abusive partner being able to track a woman’s location through her car.

Noting female suburbanites’ responsibility for shopping and chauffeuring, the author writes that “the car enslaved women even as it liberated them.” At times throughout the book, she captures some of the joy that comes with being in the driver’s seat. But the disturbing future scenarios that conclude the book are consistent with Nichols’ conflicted view of the automobile’s effects on women.