Women of the Italian Renaissance held their ground

Loading...

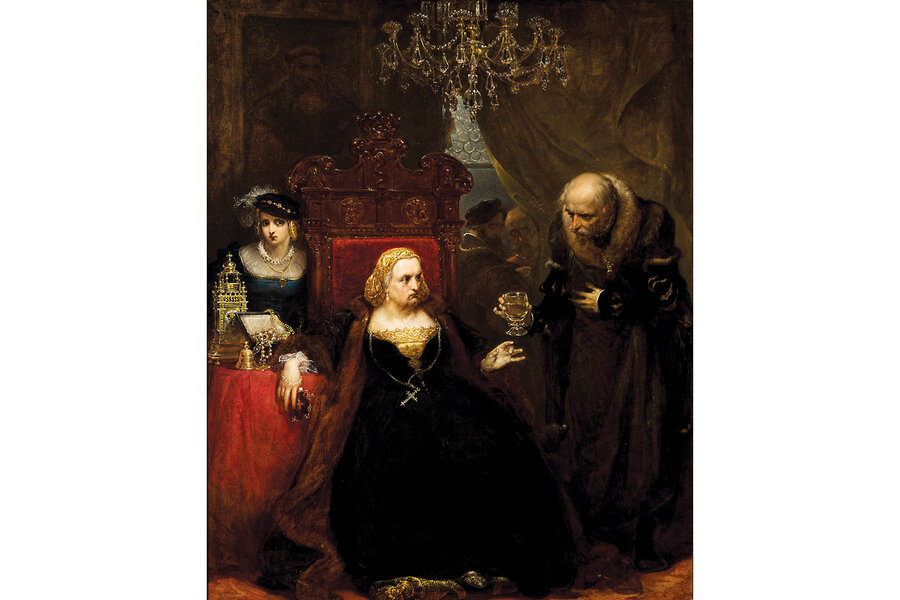

The Italian Renaissance saw a flowering of great art, music, and literature that is nearly unrivaled in Western culture. But who were the Renaissance women, whose contributions have largely gone unnoticed and unheralded?

In “Twenty-Five Women Who Shaped the Italian Renaissance,” author Meredith K. Ray vividly chronicles female poets, painters, musicians, healers, and political leaders, who finally receive their due.

Ray is the rare Renaissance scholar who writes with both erudition and charm for a general audience; the book is as engaging as a highbrow novel. Her 25 crisply written biographies reveal the creativity, ingenuity, and determination of women who were underestimated or unrecognized during their lifetimes.

The term “Renaissance” is historically associated with cultural rebirth and renewal between the 14th and 17th centuries in Europe. Ray’s portraits of remarkable women remind us that any “rebirth” associated with their vocations was hard-won. In a patriarchal era in which women were expected, at an early age, to enter either a marriage contract or a religious order, these women established significant careers.

For example, civic heroine and poet Laudomia Forteguerri, a young widow and mother of three, commanded a battalion of women fighting to protect the city of Siena against attack. Forteguerri also wrote love sonnets to Margaret of Austria, the daughter of Emperor Charles V. Both activities breached Renaissance standards of female “respectability.”

Another woman, Arcangela Tarabotti, found a way to transcend life as a nun through writing about how the intelligence of women was starkly underestimated by male civic and religious leaders. Her protests against her unjust treatment became the book “Convent Hell,” available only after her death.

Ray deserves praise for recognizing philosopher-healers alongside the poets, artists, and musicians. During the Italian Renaissance, medicine was a strange brew of philosophy, nature worship, alchemy, astrology, and herbology. This reflected the fact that many Renaissance thinkers proposed combining the ancient Greco-Roman pagan knowledge with wisdom culled from church-bound Christianity.

Camilla Erculiani effectively worked as an apothecary – what we would call a pharmacist – whose practice reflected her nature-centered philosophy. She paid a price for such an unorthodox career and was tried by the Spanish Inquisition. Although she was exonerated, she never again wrote about her work.

While the author is acutely aware of how male violence impacted women, with rape often going unpunished or unrecognized by male authorities, she also underscores how many of these outstanding women had their talents affirmed by their fathers. Lavinia Fontana, a portrait painter, was encouraged in her artistic career by her father, who was also a painter and ran an art school.

The sole criticism I would level at Ray’s book is how suddenly the narrative seems to drop off after the 25th story is told. I would have appreciated the author offering her perspectives on the relevance of these women, individually and collectively, to our time.

Ray is not the only scholar seeking a deeper understanding of women’s contributions to the Renaissance. A recent exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, “Strong Women in Renaissance Italy,” brought many achievements to light.

The exhibition catalog quotes a Venetian poet, Moderata Fonte, who is also featured in Ray’s book: “Gold which stays hidden in the mines is no less gold, though buried, and when it is drawn out and worked, it is as beautiful as other gold.”

Such emergence of female talent might well catalyze a second Renaissance as bracing as the original one.