Hometown help: What one author discovered about racial equity in schools

Loading...

Laura Meckler never intended to write a book, but then she stumbled on a story about racial equity that she didn’t want to stop reporting. The narrative unfolds in her Ohio hometown of Shaker Heights – a Cleveland suburb that over the decades has been lauded for its racial integration efforts. Did that lead to racial equity within the city’s public schools, though?

Ms. Meckler, a national education reporter for The Washington Post, started to explore that question in a story published in 2019.

“When I was done with that, I just had this feeling like there was more to say,” she says. “Even though the story that ran in the Post was quite long, I still felt like I was barely scratching the surface on so many elements.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onDo efforts to racially integrate cities help schools with equity as well? In “Dream Town,” reporter Laura Meckler examines her Ohio hometown’s tenacious push to help students.

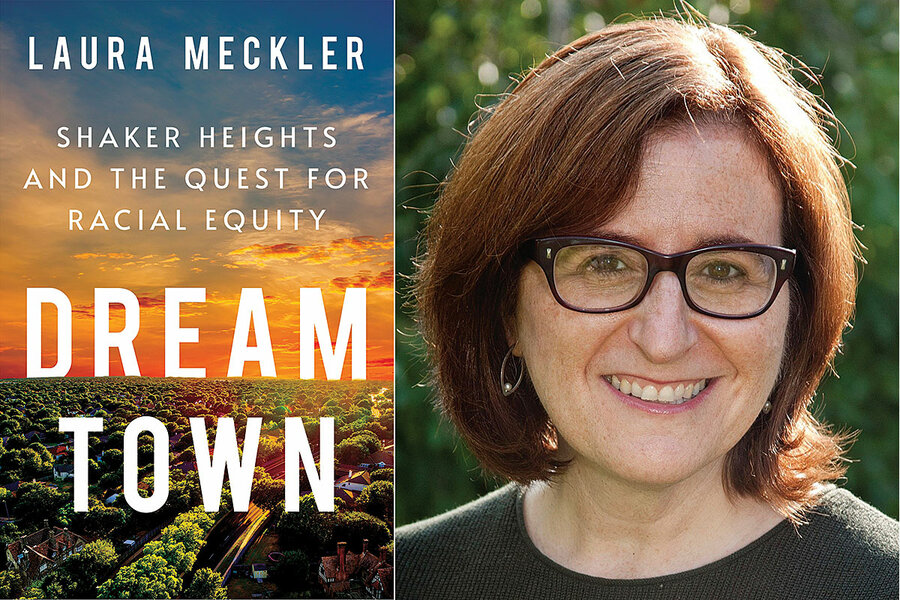

Her first book, “Dream Town: Shaker Heights and the Quest for Racial Equity,” finishes what she started with the initial newspaper story. Ms. Meckler spoke recently with the Monitor.

Your book digs deep into how housing policies shaped Shaker Heights and, in some cases, encouraged residents to band together for the sake of racial integration. Why is that so important?

Where we go to school depends on where we live, and the diversity of our schools very often depends on the diversity of our neighborhoods. So these two things cannot be separated.

I think, innately, people understand how tightly those are tied. The way it usually works is a couple gets married, and maybe they’re living in the city or they’re living in an apartment somewhere. Then they decide that they’re going to move. They’re thinking about having kids or they have young kids. Where they decide to move is always informed, for most people, by what the schools are like.

You write about two school systems within one: “Black and white students were together – but also apart.” Given that scene, what would true racial equity look like in practice?

In Shaker Heights, you have something that most of the country does not, which is this economic diversity and racial diversity within one school district. Some people are paying much higher taxes, and that’s benefiting people who have higher needs. That is a huge step toward equity. But what this book tries to do is look at it the next level up, which is what’s happening inside those walls once everybody gets into the school system together. And true equity looks like everybody having the same opportunities for success. There are a lot of systemic barriers built into schools everywhere – and in Shaker – that have stood in the way of that happening.

What are examples of those barriers?

There are issues of implicit bias. I heard so many stories from Black parents and students who had tales of assumptions being made about them. Not knowing about an advanced class that was an option. Being discouraged when somebody else might have been encouraged.

There are also institutional barriers. Some parents have jobs that allow them to stop by the school more often. Other people might be working more than one job or be so exhausted from being on their feet all day that they just don’t have the energy to go into something at school.

The book also examines the school district’s more recent “detracking” efforts, which put students of mixed abilities in the same classroom. From your observations, what was the key to making that work?

I’m not sure we yet know whether it was successful or not. Truthfully, I think that the detracking initiative was pretty poorly implemented.

One of the lessons actually from the detracking initiative is that if you’re going to try to do some hard things like this, you really need to do it very carefully and in a way that communicates with people and brings people along. You’re never going to win over everybody.

To the extent that it did work, though, ... it was because of the commitment of those teachers, I think, who were working really hard to do differentiated teaching. So, for instance, one person might reflect on a novel by making a podcast about it. Somebody else might write a paper. Somebody else might deliver a speech. Someone else might do a graphic novel-type drawing.

You note that Shaker Heights is far from perfect, but it’s still trying. What can other communities learn from the city’s racial equity efforts?

If this is something that’s important to you – to try to create a more equitable community and a more equitable system – it takes work and it takes commitment. You have to sustain that commitment over a long period of time. There is no one magic bullet, perfect solution.

I concluded that this is really a story that’s more hopeful. Even if these problems don’t get solved, the fact that they’re still working on them and pushing the ball forward ... that is meaningful, and it puts them ahead of a lot of this country.