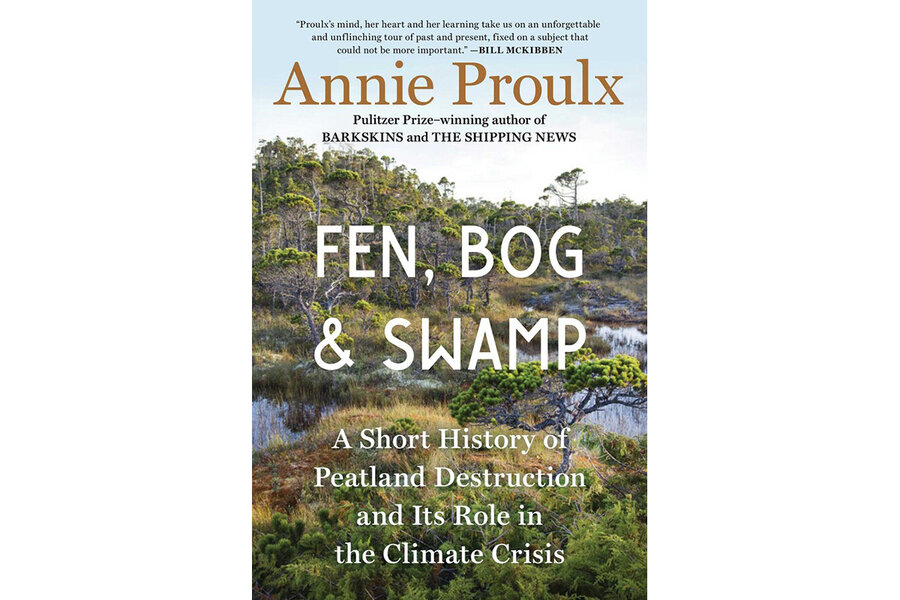

Don’t drain the swamp: Annie Proulx extols the virtues of wetlands

Loading...

Swamps, bogs, and marshes have long been portrayed as uninhabitable, impenetrable, and menacing – as places to avoid. For centuries, humans drained wetlands to plant crops and graze livestock, and the land was increasingly claimed for housing and later for commercial development.

Yet the importance of wetlands to the global ecosystem can’t be overstated. Peat bogs, for example, sequester large amounts of the carbon dioxide and methane that are driving climate change. As Annie Proulx writes in “Fen, Bog and Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis,” wetlands are vital to the well-being of the planet. They can help “soften the shocks of change.”

As she points out, wetlands have faced “a global storm of greed,” with humans intent on draining, stripping, and filling in these spongy landscapes, which appeared to be of little value. “Since the fifteenth century when feudalism began to give way to nation-states, Western capitalism and imperialism, we have heard that peatlands are worthless because that same land drained is valuable for agriculture,” Proulx writes. “We are now in the embarrassing position of having to relearn the importance of these strange places.”

In brief and luminously written chapters, she looks at some of the outbreaks of that storm of greed, starting with the destruction of the English fens and the indigenous peoples who lived there for thousands of years. In all the book’s sections, the righteous anger of a climate watcher is blended with the beautiful prose this author has been writing for 40 years.

“The fen people of all periods knew the still water, infinite moods of cloud,” she writes. “They lived in reflections and moving reed shadows, poled through curtains of rain, gazed at the layered horizon, at curling waves that pummeled the land edge in storm.”

But the main focus of this slim book is what Proulx inimitably refers to as “the despicable, exquisite, confounding, ever-changing swamp,” from the evocatively named Great Dismal Swamp, which straddles southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina, to the Great Black Swamp in the Midwest, to the Okefenokee in the Southeast. She writes of tramping the Okefenokee, “It was a mat of sphagnum moss, and although some people say walking on it is like walking on a water bed, I felt its billowy heave was more like a wave of dizziness before you pass out – a very slow falling sensation although you remain upright.”

She laments the destruction a century ago of the Kankakee Marsh (“the Everglades of the North”) in northern Indiana: “When they finished obliterating the Kankakee, the new unbending canal system was ninety miles long,” Proulx writes with a combination of sadness and disdain, “a mere 36 percent of what had been the river’s varied and complex natural length of 250 miles.”

More than half of America’s wetlands have been wiped out just since the 1980s, and as Proulx admits, it’s tempting to “believe with hopeless conviction that the past cannot be retrieved.” But a stubborn thread of wary optimism runs through “Fen, Bog and Swamp.”

Proulx reminds her readers about “how eagerly nature responds to concerned care.” And she points out that “the public is beginning to regard the natural world in a different way. The ‘rights of nature’ is a legal concept that is gaining international standing. The United States is among dozens of countries that have committed to some ‘rights of nature’ laws that allow citizens to sue on behalf of lakes, streams, ocean reefs, swamps.”

It’s not too late to start showing care for wetlands – particularly with powerful books like this one pointing the way. This is a stark but beautifully written “Silent Spring”-style warning call from one of our greatest novelists.