Q&A with Julia Flynn Siler, author of ‘The White Devil’s Daughters’

Loading...

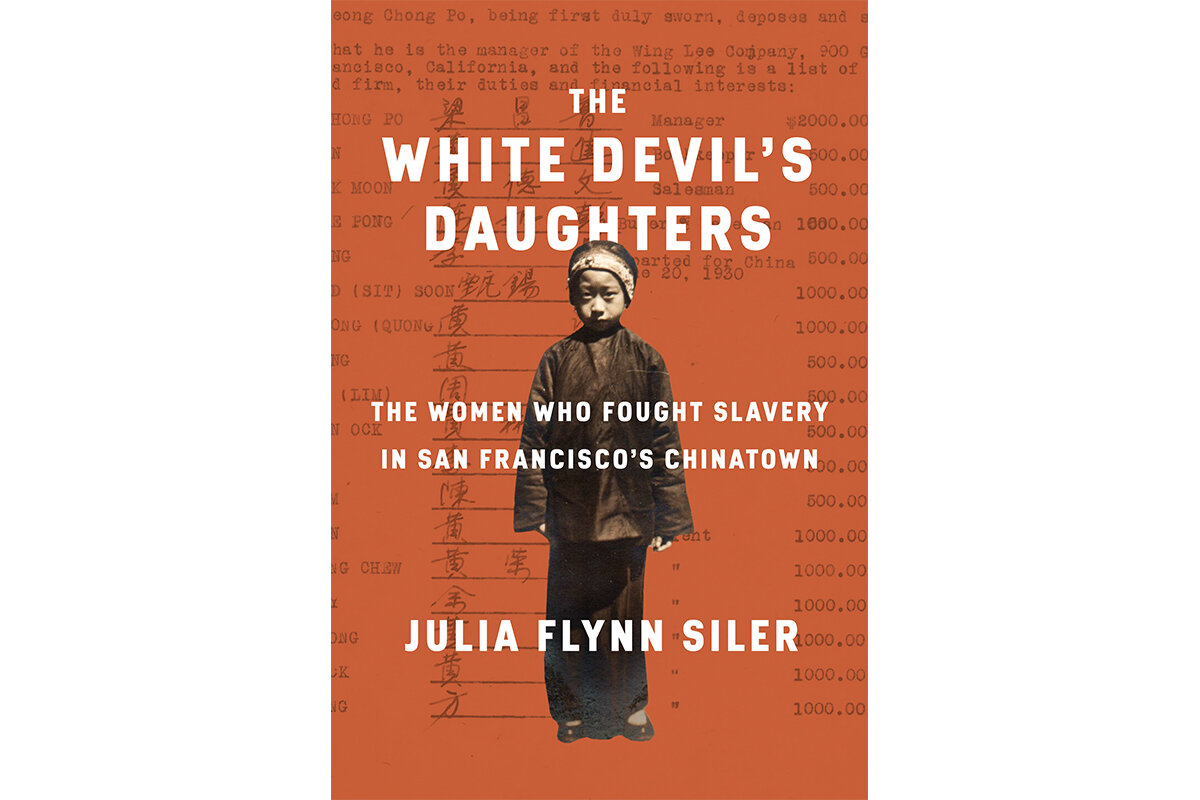

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, women from Asia were trafficked in San Francisco’s Chinatown, while authorities looked the other way. But not everyone stood by. Two women, one white and wealthy, the other a Chinese survivor of sex trafficking, created a pioneering rescue mission called the Occidental Mission Home. The women’s story is told by Julia Flynn Siler in “The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown.”

How did you discover this story?

I’m a native Californian and a local girl, and I’m fascinated by the history of [the Bay Area]. I came across this account by [rescue mission founder] Donaldina Cameron describing how she led 60 girls and young women across a burning San Francisco after the earthquake of 1906. Her voice was so vivid and so strong that it brought to mind the question of why hadn’t I heard about her before and how I could learn more about the rescue home that she ran in Chinatown.

How did the sex trade develop?

In the 1870s, there was one Chinese woman for every 10 Chinese men in San Francisco. Criminal networks saw an opportunity to make a profit, and they built [sex trafficking] into a big and thriving business with the help of local policemen, immigration authorities, and the city administration, which was deeply corrupt. Chinese people were not allowed to own property, and most landlords would not rent to them. Chinatown was the densest part of the city and home to about 12,000 people. The vice district overlapped with Chinatown to a great degree. There were all sorts of people who would come there to buy opium and sex.

What motivated the women who founded the mission?

They were Christians trying to live in the humble and compassionate way their faith suggested they should, and they saw social injustice in the horrific treatment of girls and young women. They faced extremely difficult conditions. The house was constantly threatened with bombs. At one point Cameron had an emotional breakdown. Over the years, she struggled on an emotional level to carry on the work. But she was very tough-minded and stubborn. She was not going to back down in the face of these threats.

A Chinese woman named Tien Fuh Wu led the mission with Ms. Cameron. What was her role?

I don’t think Cameron could have successfully run the home without Chinese colleagues. They spoke Cantonese, and they could directly communicate with vulnerable and traumatized women and girls. For Wu, who’d been sold by her father, it was a lived reality for her. When she talked to other vulnerable girls, she could say, “I’ve been through this, too.”

What else did they do to fight trafficking?

They exerted power in a direct way. They effectively used the newspapers, shaming politicians by holding up to them that trafficking and sex slavery was going on with their knowledge close to their homes.

What can we learn from these women?

We can learn about grit, resistance, and how to oppose racism. These women popped their comfortable bubbles. They literally came down from San Francisco’s Nob Hill and other wealthy areas and tried to help. They didn’t always do the right thing, and they could be patronizing. But we can learn from them how it’s important to really feel what other people are going through.