How to save politically ‘mixed marriages’ in Trump era

Loading...

For years, Jeanne Safer has received letters from people whose personal relationships have been upended by political differences. She’s heard of engagements being called off, siblings who are no longer on speaking terms, and a pending divorce because the wife wouldn’t let her husband watch Fox News in the basement of their three-story home.

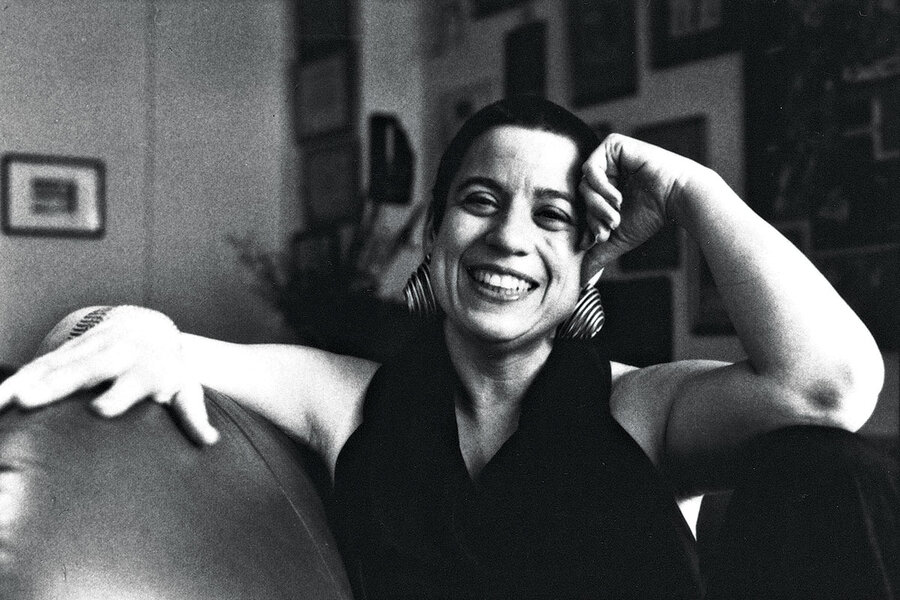

The reason they’ve reached out to Ms. Safer, a psychotherapist, is because she herself is in a politically “mixed marriage.” For the past 39 years, the liberal New Yorker has been married to Richard Brookhiser, a senior editor at National Review. Now she’s parlayed those experiences into a new book, “I Love You, But I Hate Your Politics: How to Protect Your Intimate Relationships in a Poisonous Partisan World.” Ms. Safer’s book isn’t a “Republicans are from Mars, Democrats are from Venus” tract so much as it is a guide to what true love entails.

The Christian Science Monitor spoke with Ms. Safer by phone about the ideas in her book. (This conversation has been edited and condensed for space.)

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onLearning to respect someone for who they are, not trying to remake them in your likeness, is something most people have to learn about love. It applies to politics, too, author Jeanne Safer says.

Why do people take politics so personally?

Because you want the people that you love to be like you and to like you. We are compelled to change people’s minds because otherwise we have to accept enormous limitations on the effect that we can have on other people. But if you think about it – this is my great revelation – it’s like trying to make somebody fall in love with you who doesn’t. You can’t do it! You aren’t going to persuade somebody who has a different view of the world, and once you realize this you can then begin to have actual discourse. It’s in a way, it’s radically respecting the other person’s selfhood.

I learned this from personal experience because I’ve been married to a conservative commentator for 39 years. And I change people’s minds for a living, that’s what I do. So of course I thought, with total arrogance, that I could certainly change his – an intelligent guy like this. And for the first, I would say probably for the first 10 years, I really gave it the old college try.

With you and Richard, what is the difference of values between you?

If I thought that we had fundamentally different values, I couldn’t be with him. I think this is the main idea in my book. I have a chapter called “What is a core value?” And to me a core value is not your political philosophy.

There was one person I interviewed who really embodied this, a young woman, and her father was a dear friend of mine. He died a very terrible death. He had five brothers and sisters, all of whom were progressives and she totally identified with these people. He had one brother who had moved to the South, converted to evangelical Christianity, and was in the military. Guess who was the only person who showed up to help her? And he left his wife and his five children far away and came. Not one of the progressives – she knew them well – lifted a finger. And this was not lost on her.

They had been fighting on Facebook about all kinds of stuff. She made a heartfelt apology to him. She said, “I have misjudged you.” So she found out that they really did share core values even though they had a lot of things not in common, the things that were the fundamental human values.

So, to understand where people are coming from, you have to have mutual respect?

You don’t start trying to understand the other person, you first start understanding yourself. Your own prejudices, your own resistance, the way that you are obnoxious. For instance, if you take an article from your point of view and you stick it in the face of the other person at the breakfast table, or send it to them on e-mail or whatever, and you expect that this is going to be a way to have a dialogue. It has never worked yet.

Has social media made it more difficult to have real dialogue?

I have eight commandments. And one of them is, “avoid social media.” Do not read what the other person says. You know what they’re gonna say. Consider it like their diary. Stay away from that and, whatever you do, do not “unfriend.” It is a disaster. People are devastated. It’s very hard to fix. And if you have something to say to somebody, I say go analog. That is, write him a letter. Call him on the telephone. Or go and see them. And I counsel people to do this. And I think I saved a few relationships that way.

So it is possible to preserve relationships in this fraught era?

I did not expect this because I’m not the biggest optimist. I can give you some examples of some of them where I really thought it was hopeless. I often told them what to do. You know like, if you love your sister and she’s on the left and you’re on the right, don’t just keep yelling, “Trump is everything.” Think about the fact that you were dear friends when you were children.

I said, “What are her good qualities?” And the brother said, “She has a great sense of beauty and she lives a life of the mind.” And I said, “How about telling her that?”

He’d alienated everybody else in the family. Why don’t you tell her that this is something too precious to lose. And I wrote three months later and he said, “We’re avoiding politics and we’re doing much better.”