Louise Penny’s unlikely motto for murder: ‘Goodness exists.’

Loading...

| Knowlton, Quebec

Fans of bestselling author Louise Penny make pilgrimages across the Eastern Townships of Quebec in search of Three Pines, the rural village where her elaborate mystery novels are woven.

It would be easy enough to turn up in Ms. Penny’s real-life town of Knowlton, with its bookstore, its bakery, and corner bistro, and feel that Chief Inspector Armand Gamache and the townspeople in her crime series might jump off the pages and pass you on the street.

“People often ask me, ‘Does Three Pines exist?’ I have to tell them it doesn’t,” says Penny. For her, in fact, the town has always been an allegory, ever since the first book was published in 2005. And even though she admits it can sound “woo woo,” she calls Three Pines not a place, but a state of mind. It’s where she lives when she chooses to be kind, she explains.

Why We Wrote This

You can’t find Three Pines on a map – whether in fiction or in real life. But, our Canada correspondent says, ‘From the moment [Penny] opens her front door, with a warm smile and her golden retriever, Bishop, panting at her side, I know I’ve arrived at Three Pines.’

From the moment she opens her front door, with a warm smile and her giant, 14-year-old golden retriever Bishop panting at her side, I know I’ve arrived at Three Pines.

Penny’s 14th book – in 14 years – goes on sale Nov. 27. “Kingdom of the Blind” revolves around an elderly woman and her will – and of course a murder that Gamache needs to solve. But like all of her books, the whodunit is secondary to the subjects of goodness and decency, the things taken for granted, and the blind spots in life.

These themes have always pushed her books beyond the mystery genre, earning her readers who are ultimately drawn as much to Gamache’s masterful detective work as to Penny herself – her outlook and the fearlessness and generosity of spirit reflected in her characters.

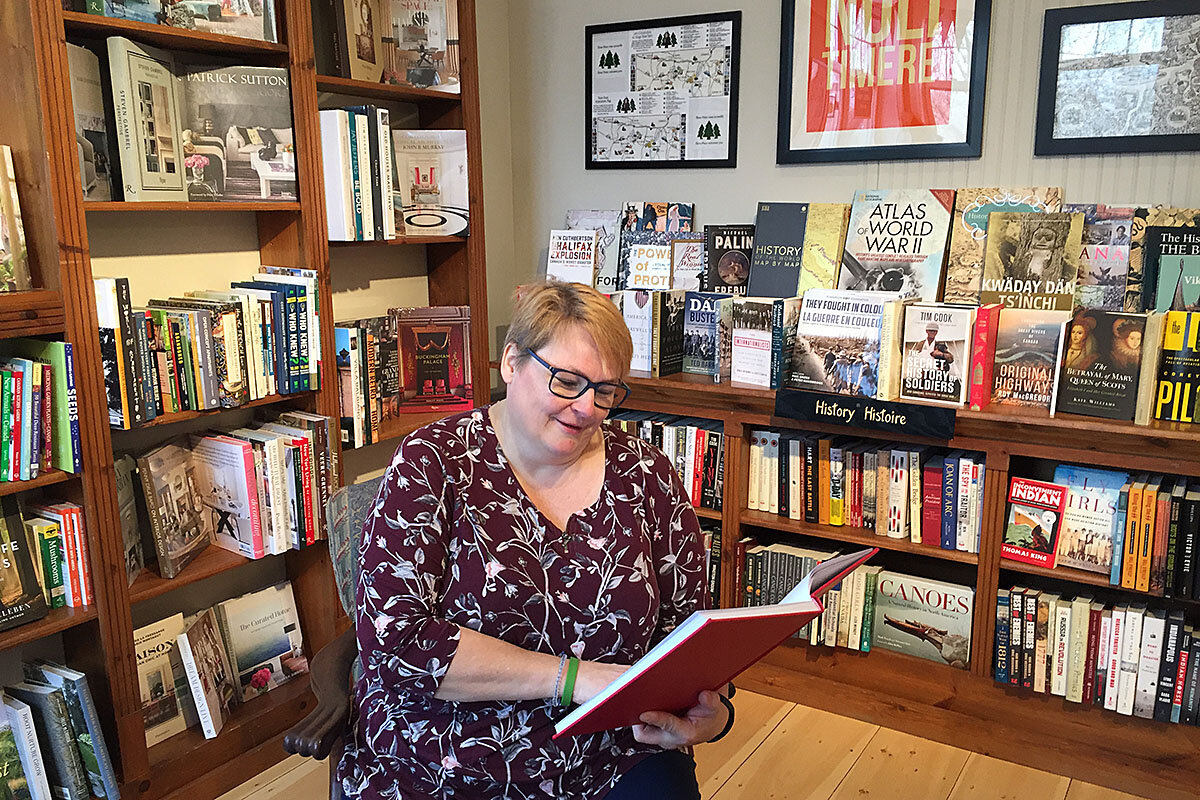

Inside Brome Lake Books in Knowlton, owner Lucy Hoblyn has set up a Louise Penny corner, where she says people from all over the world descend, increasingly each year. “Every book I read I see Louise in it, her humor, her passion. Three Pines is for her, her place, the place where she came and re-started her life.”

Much of Penny’s inspiration has come from the poet W.H. Auden. It was his poem to Herman Melville that touched her, before she started the series. This was after a battle with alcoholism; a hard, two-decade career in journalism; and a bout of self-loathing that not only made her dislike the cynical side of herself, but herself altogether, she says.

And she read these words: “Goodness existed: that was the new knowledge. His terror had to blow itself quite out/ To let him see it.”

She had just turned the corner. “I was close enough that I could still feel the vestiges of the terror. But I was also feeling that incredible awakening of hope. Of how beautiful the world is and how beautiful people are.”

She met her late husband, Michael Whitehead, who coaxed her to quit her job and fulfill a lifelong dream of writing a novel. And that’s how Three Pines started to take shape. Her copy of Auden still sits next to her laptop, on the wooden table where she writes each morning – a minimum of 1,000 words a day. It is literally falling apart.

A safe place, despite the murders

Three Pines is not just a place to find goodness, but it is safe – perhaps ironic since it’s the setting of more than a dozen murders. And yet a sense of community, and living a good life, always prevails in Three Pines. That’s how Ms. Hoblyn says Penny lives within her real community. (On the day of our interview, she is trying to fob one of the wreaths she made for a fundraiser for a local shelter on her assistant, Lise. Penny rose at 3:30 a.m. to first get in her daily writing.)

“That sense of community, the yearning that we all feel, I think that one of the reasons the books are successful across borders and across cultural groups and ethnic groups and language groups is because as humans we have certain things in common and one of the things is I think we really want to belong,” says Penny, who has won multiple awards for the series, including five Agatha Awards. “I get so many emails from people about the bistro and about wanting to sit in the bistro with that group of friends where people are accepted.”

Her main character was inspired by her late husband, who was the director of hematology at Montreal Children’s Hospital, what Penny calls “the worst job in the world, including homicide detective.” And yet he chose to live with joy, like Gamache, because he understood the privilege to make the choice.

When she set out to create her central figure, she recalled reading that Agatha Christie grew weary of her main character, Hercule Poirot. She remembers thinking: “If the books are published and I live with him for the rest of my life, do I really want a main character who I find really annoying?”

She took many walks, and it occurred to her: “Just to create a character I would marry, give him all the qualities I admire, not just in a man but in a human being,” she says. “And not a perfect man, because that would be very annoying, but someone who struggles to be decent.”

Penny lost her husband, who was diagnosed with dementia, in September 2016 after 20 years of marriage. She had planned to take more time off than she did, when she found herself next to the fireplace, Bishop at her side. A thought sprang to her mind from dealing with her husband’s will. “We were talking about executors, and someone said in passing, ‘Did you know that anyone can be an executor?’ And I thought, ‘Now there’s an interesting idea.’ ”

She returned to her wooden table with a feeling she hadn’t had in a long time. “The terror had blown itself quite out,” she says, returning to Auden. “And I could feel light again, levity. I was still sad but that anticipatory grief was gone, the dread. So I could just write with joy.”

Her new book has already been received with rave reviews, but getting to this place was not seamless. As a radio journalist, she says her every word was prescribed to the second. She was full of anticipation when she gave up those confines. “I thought, ‘oh great, now my free spirit can come out.’ It turns out I have no free spirit. It’s very caged and likes it that way.”

Penny suffered writer’s block for five years, under the pressure of writing “the best book ever written, that was the plan, the top of the list.” One day she looked at her bedside, years after her husband stopped asking her how “the book” was going. She saw among the pile the golden age crime novels she’d been devouring since she was 8.

She also credits a group of women artists she met in the countryside after she moved from Montreal, who called themselves “Les Girls,” for giving her a window onto the creative process. Their influence is reflected in the strong female characters that play defining roles throughout her series. “I got to see some triumphs, but I also got to see some big, stinking flops. Really what I got to see was that no matter what happened, they got out of bed. It didn’t kill them.”

‘Nobody would [read] a crime novel set in Canada’

When I mention Penny to friends and family in the US, many say they read her avidly or know someone who does. In Toronto, she is unknown among all the new friends I have met. Indeed, she made The New York Times bestseller list before any Canadian one.

“When I was trying to sell the books early on and everybody said ‘no,’ one of the comments I got from a lot of Canadian publishers was that nobody would be interested in a crime novel set in Canada,” she says. “Some had invited me to set them somewhere else. Mostly the States. And to be honest I was so desperate to be published, I considered setting it somewhere in Vermont. I remember thinking: How different can it be? It’s just 20 miles across the border.”

Today she thinks the fact they are set in Canada – with generous nods to Canadian artists, history, and Quebecois identity – is among their greatest selling points. “It’s very humbling to realize how many of my beliefs I'm willing to compromise,” she says, laughing.

She says she would not recognize the person she once was, “thankfully.” “What I mean is the outlook on the world, the sense that people can’t change. And that's one of the themes in the books too. People do change, for the worse, but they change for the better too.”

As I’m sitting with her, feeling as though I could go on doing so all day, I think that what really draws readers to Penny’s books is neither its Canadian history nor its intricate resolutions but the chance to hunker down for several hours with Penny herself. Here’s a person who overcame self-loathing, who published her first book at age 46, who still carries around that universal self-doubt and shares it generously, always with a sense humor, as well as the occasional expletive. Yet she always comes back to her driving message: “Goodness exists.”