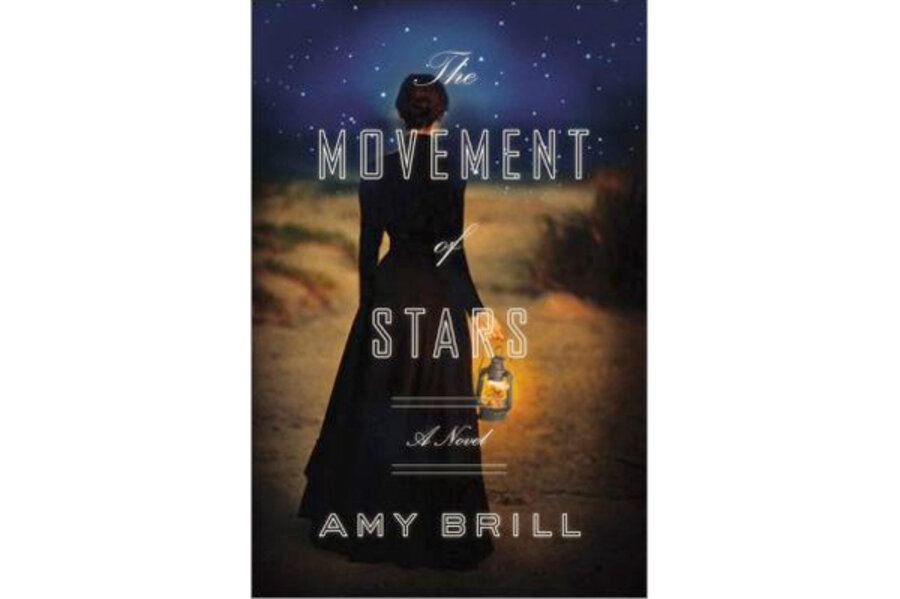

Hannah Price has raised sleep deprivation to an art form in Amy Brill's strong debut novel, The Movement of Stars.

By day, she serves as assistant librarian at the Nantucket Atheneum. By night, she sweeps the skies with her dad's old telescope, trying to be the first to spot a new comet and win the king of Denmark's prize. In between, she recalibrates chronometers for whaling ships, takes care of the house, and deals with her family's failing farm. Money is so tight that at the beginning of the novel, Hannah repairs one of the crosshairs on her telescope with a “sticky strand of cocoon.” "She was used to the echoey ring of fatigue."

No wonder her hair and temper are a mess and she burns meals.

Apart from missing her twin brother, who shipped out on a whaler three years earlier, Hannah would have said that she was content in her life as part of the island's Quaker community until two things happen: One, her father, who taught her to love astronomy, has decided to remarry a wealthy widow in Philadelphia. Hannah can either set aside her scientific ambitions to move with him or marry, giving control of her life to another man. And two, a second mate from the Azores, Isaac Martin, asks Hannah to teach him the principles of navigation.

Their nighttime lessons scandalize a community that, while abolitionist, isn't exactly as above prejudice (or gossip) as it liked to pride itself on being.

Brill, a TV writer and producer, writes that she based Hannah's work on that of Maria Mitchell, the first female astronomer in America. Brill conveys both Hannah's love for her work and the cramped nature of the society that she outgrew without realizing it.

“My sight has been parched,” she thinks when looking at the sky through a new refracting telescope in Cambridge. “I had not known. And now here was the quenching light.”

The same was true, she uncomfortably discovers throughout the novel, of her heart. The romantic subplot is pure fiction, but Brill sticks reasonably close to the facts of the day. At least there are no oceanside weddings presided over by repentant clergy, who have miraculously seen the error of their racist ways.

At one point, Hannah thinks of her mentor, the real-life figure William Bond, that he “was living proof that the eye was the mightiest of all the tools at an astronomer's disposal. If anyone had ever accomplished more with less, she did not know of it....”

Hannah, meanwhile, has no chance of higher education, no observatory, no money, and no instruments beyond her dad's battered old telescope. If she ever had time to look in a mirror, another candidate might suggest itself.