Zeke Cooper’s life hasn’t turned out quite like how his ambitious mother had planned. Undone by twin disasters – divorce from his childhood sweetheart and the drowning death of his twin, Carter – the 42-year-old can’t see a future any more.

The big question, as he puts it, is: “[H]ow did the smart boy with a full scholarship to the University of Virginia end up living in a converted shed in his mother's backyard and working on the line at the Dover elevator plant?”

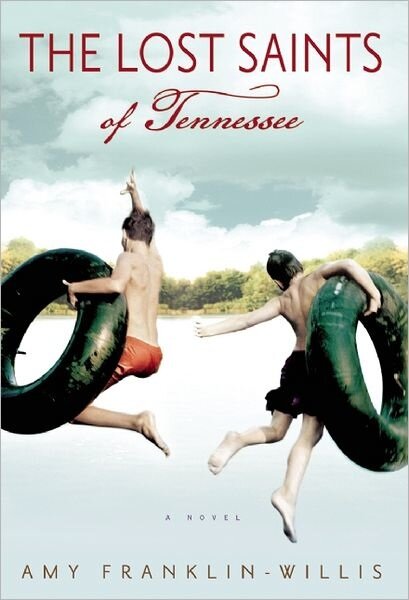

The Lost Saints of Tennessee, told mostly from Zeke’s viewpoint, with a few salient facts thrown in by his estranged mother, Lillian, looks at the Cooper family history from the 1940s to the 1980s and how things went so very wrong.

When the novel has opened, Zeke’s had enough: “My daily choices have evolved from whether to have chili or a Swanson's Hungry Man dinner to kicking around suicide methods.”

He can’t leave his brother’s elderly dog, Tucker, behind, so the two set out to Pigeon Forge, where Zeke’s suicide plan doesn’t quite come off as expected. From there, Zeke and Tucker head back to a relative’s farm in Virginia – the last place he can remember feeling hope.

“The Lost Saints” is a “Southern novel,” in terms of being filled with RC Cola, Moon pies, McDonald's drive-through, hummingbird cake, and the Piggly Wiggly. But any bright kid making it to middle age can easily relate to battered Zeke and his bafflement about what he’s supposed to do now.

Franklin-Willis tries too hard to create a happy ending for her worn-out hero, but she excels at making readers care about her characters, especially the ones who have made the biggest mistakes. And after all, it would be downright curmudgeonly to begrudge Zeke a little happiness.