Seismic waves of mistrust

Loading...

"Why do they hate us?" Americans sometimes wistfully wonder about our poor image in the Islamic world. (Or at least we did before Guantánamo, Abu Ghraib, and extraordinary rendition gave terrorists plenty of ammunition with which to work.) But if you're still wondering, pull up a chair. Kurdish grocer Sinan Başioğlu would be happy to explain.

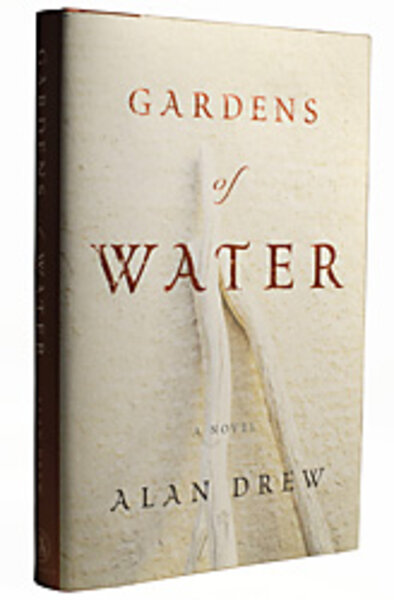

The protagonist of Gardens of Water, the debut novel by Alan Drew, hates everything about Americans, except Chevrolets. He blames the United States for his father's death at the hands of M-16-wielding Turkish soldiers, and a Western-owned supermarket has just about put his store out of business.

But Sinan is about to be in the excruciating position of having to be grateful to Americans.

The novel opens with the coming-of-age ceremony of Sinan's son, Ismail. Much to his chagrin, his wife informs him that they must invite the American Roberts family who live in the apartment above. (Unknown to either set of parents, their teenage daughter, Irem, has been meeting secretly with 17-year-old Dylan Roberts.)

The description of the party is mouth-watering: "On one table, rice and pine nuts spilled out of stuffed peppers, dolmalar sat stacked on tea saucers like a pyramid of grape-leaf cigars, Circassian chicken floated in walnut sauce and pools of olive oil...." Fifteen-year-old Irem, who has a Cinderella complex, does the dishes.

That party is the last bit of normal life for both the Başioğlus and the Robertses. Later that night, the 1999 earthquake that killed up to 17,000 people hits, destroying everything the Başioğlus own. Sinan, who couldn't sleep, watches in horror as Ismail flies out an open window.

Three days later, he finds his son, alive in the rubble, wrapped in Sarah Roberts's arms. (How one regards this coincidence will determine a reader's emotional response to the novel.)

That terrible disaster is the catalyst that Drew uses to detail the fault lines in the Kurdish and American families. The collision of the two families is as disastrous as the collision of tectonic plates.

Sarah, Ismail recounts to Marcus and Dylan in one of the novel's most moving passages, sacrificed herself for the little boy. Having lost everything, the Başioğlus become dependent on Marcus Roberts, who is a leader with the relief effort. Marcus offers them shelter and even cares for Sinan's injured foot himself, but Sinan still instinctively mistrusts the Americans.

At the refugee camp, Ismail becomes interested in Christianity; meanwhile, Irem sneaks off with Dylan.

Drew, a former teacher who arrived in Turkey four days before the 1999 earthquake, volunteered in a tent city similar to the one in which the Başioğlus take shelter.

He recreates both the disaster and the transient world of the survivors with impressive skill. And there are wonderfully detailed clashes of culture, as when Sinan comes home from visiting Istanbul with Ismail to find his head-scarf-clad daughter watching "Buffy the Vampire Slayer." She argues that Buffy is dispatching evil. "There was killing and there was kissing, enough for him," Sinan decides, switching off the TV.

But the relationship between Irem and Dylan never really escapes the page. And given the disasters that follow in its wake, it needed to resonate like a tuning fork in an organ shop. And while Irem's desire for validation and freedom – universal to teenagers irrespective of culture – are well-written, her jealousy of the pampered Ismail gets pounded too hard. Her brother was buried alive for three days; one would imagine she would be thrilled to see him for at least five minutes before going back to her habitual resentment.

Sinan's emotional life at times is similarly problematic: His bitterness and anger tend to seem more real than his love for his daughter. "He was so sick of death. There were people in the world that never had to face death, except in old age.... He hated and wanted to be one of those people."

The tenuous friendship between the two dads, which doesn't survive Marcus's paternalistic attitude and the fundamentalist cast of both their faiths, is actually the most interesting of the novel.

Religion, particularly of the fundamentalist variety, does not fare well in "Gardens of Water," which is named for a description of heaven in the Koran. But the clash between Islamic tradition and the Westernized present, as embodied in the Başioğlu family, is one that certainly resonates with our times.

• Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.